Who Writes the Books?

Race impacts every process of publishing a book

The publishing industry incorporates a history of marginalising ethnic group authors throughout the method of publishing their book.

This results in authors being influenced to perpetuate stereotypes, solely writing about stories surrounding race, being involved in a pattern of tokenism and being attached to generating an answer for the shortage and variety within the industry.

Book of the Year winner 2020, Candice Carty Williams says “The questions I was asked in interviews and at events used to get me. Many people wanted me to tell them why the publishing industry was so bad if you were a Black author, it took a long time for me to be able to say that it wasn’t my problem. I remember once saying that nobody asked Ian McEwan why the publishing industry wasn’t representative. After that, people asked me about the industry less” The constant quizzing became draining “They were hard, all those questions. I just wanted to talk about the book and my craft but instead, I was having the explain how the publishing industry works.”

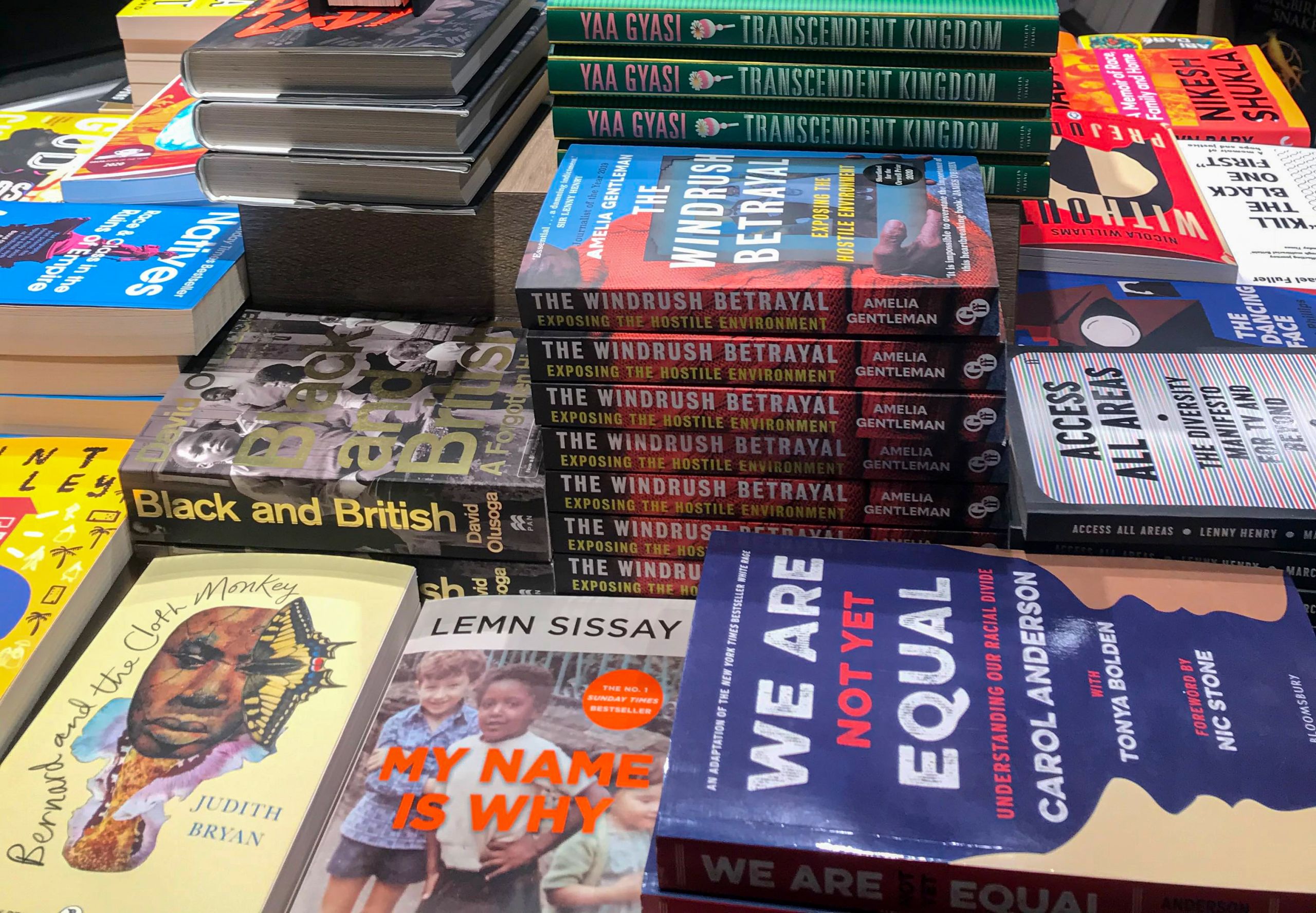

The Black Lives Matter movement facilitated awareness within the number of books that were published by Black authors, which called to attention the reasoning and process behind why Black authors were published infrequently before.

Black Lives Matter

IIn May 2020, the Black Lives Matter movement generated consciousness for worldwide systemic inequalities, primarily in the conduct of police towards citizens. This curiosity trickled down through different avenues, many institutions outside the police opted for an alliance with equality and shunned people who didn't, while the public swayed towards educating themselves through different sorts of art, like books.

Black writers like Layla F Saad and Akala topped the bestseller charts while the public was bombarded with continuous booklists on learning about a way to be anti-racist. These lists swept through the British media widening discussions within the publishing industry about diversity and inclusion.

For instance, a Twitter campaign called #Publishingpaidme, where authors disclosed on social media how much they were paid for their work revealed racial disparities. White American science fiction author John Scalzi received $3.4million in 2015 for a 13 book deal. While award-winning Black science fiction author, N.K Jemisin tweeted she received $245,000 for a combination of 8 books.

The movement shined a light on many authors and influenced a soar in book sales regarding race, identity, and cultural history. During the protests, Reni Eddo-Lodge became the first Black British author to top the best-sellers chart since 1998. Bernadine Evaristo and Candice Carty-Williams are the first Black authors to win top British book awards, one year on, books by Black authors remain in the UK bestsellers chart. While these achievements should be celebrated, they do highlight the unique challenges that these authors face. Evaristo was a joint winner of the 2019 Booker prize with Margaret Atwood but was identified as the 'another author' by a BBC journalist. Evaristo tweeted “how quickly and casually they have removed my name from history” finishing with “this is what we've always been up against”. This is only a snippet of what authors of colour experience.

Pls RT: The @BBC described me yesterday as 'another author' apropos @TheBookerPrizes 2019. How quickly & casually they have removed my name from history - the first black woman to win it. This is what we've always been up against, folks. https://t.co/LxxDBJrUYh

— Bernardine Evaristo (@BernardineEvari) December 4, 2019

Diana Evans has been writing novels for over 15 years, she was awarded the Orange Award for New Writers in 2005 and her most recent novel, Ordinary People was shortlisted for the 2019 Women's Prize for Fiction.

Diana fell in love with writing at the age of 14, she wrote in a journal while discovering that she enjoyed writing poetry. Writing came naturally to her, it became a bubble of tranquillity where she found a “soothing way to express feelings, observations and thoughts”. After a dissatisfying job as a journalist and an urgent response to bereavement, Diana leant towards writing short stories in addition to poetry, which led to her first published book, 26a.

Marketing for 26a proved to be somewhat of a discouraging requirement. Diana is of mixed heritage, and this became her identifier at the time, “When 26a came out, I was marketed as 'the voice of multicultural Britain'’” This is something which is not necessarily new within the publishing industry. Writers of colour are identified as a spokesperson for their race, which can be empowering yet damaging. Writers are multifaceted and race is only a part of that, to be purely identified based on your race is something white authors never have to experience.

Diana instantly saw the flaws in being identified by her race, “It was a label I didn't feel comfortable with. It implied, I was a mouthpiece for anything to do with race and multiculturalism in Britain and I didn't feel like that at all, still don't, and nor should I”. She continued, “I find the race label oppressive, reductive and instructional. Race does not belong to Black people. It is a world problem and whites must carry it too, perhaps more so because of white privilege”.

She referred to one of the lowest moments in her career being related to being constantly identified as something she considered to be disheartening “at literature festivals or events where I have been called on to be the voice of multiculturalism, Blackness and diversity. I have found it erasing, flattening and short-sighted” While it is discouraging to be singled out based on race, it is also an important feature within a book. Black, Asian, and ethnic minority protagonists are infrequent characters that should be experienced. In addition to Diana’s race, she was being identified as the image of multicultural Britain just because she was writing about Black characters.

She made a conscious choice to include Black main characters in her most recent novel, Ordinary People, “I had a desire for a book to exist that captured the everyday lives of Black-British people, without assigning them the stereotypical heavy racial themes (while also not ignoring these themes), and without describing them as outsiders. I wanted to write from deep inside their lives and thoughts and give them the respect of space on the page, to present their humanity in the face of the long-term dehumanising effects of racism and colonialism over time” Black main characters doing ordinary activities is somewhat of a scarce subject in books, the characters are known to be surrounded by some sort of oppression.

She continued, “The invisibility of Black characters in British fiction troubles me and I have a desire to correct this, to fill the gap”

Diana Evans Photo Credit: Charlie Hopkinson

Diana Evans Photo Credit: Charlie Hopkinson

Diana Evans Photo Credit: Charlie Hopkinson

Diana Evans Photo Credit: Charlie Hopkinson

Expectations

In 2015, the Writing the Future: Black and Asian Author in the Market Place report found that producing fictional books that conform and perpetuate stereotypical views of ethnic minorities were more likely to be published. The report was a study into the racial inequality with the publishing industry, commissioned by London based writer’s development agency, Spread the Word. Editor of the report, Danuta Kean said to The Guardian. These books are published “under the presumption that white readers cannot relate to stories that do not involve these topics” and “as if these were the primary concerns of all BAME people”.

Authors have relayed how expectation influence their writing, Ifran Master, author of Out of the Heart told BookTrust “the expectation is that you’re writing a book that will be a bit more ‘exotic’ and that you will be writing a book representing ‘all’ your people with no distinctions of whether you’re from a particular ethnic group or religion. Throw in a heavy dose of political correctness, middle-class politeness, the inexperience of working with POC, non-existent marketing budgets, publishing trends and the ‘one POC writer at a time, please’ school of thought, then you often have a total miscommunication between POC writer and publisher”. The reasoning that white readers will not relate to ethnic minority authors, coupled with the systemic inequalities presents a plethora of issues. All these topics make up how a person of colours’ writes their book to how it is published.

Marginalised authors dominate writing about race, it is difficult to be published if you write outside of this and it is difficult to just be viewed as a writer. Orange Prize nominee and author of Strange Music, Laura Fish expressed an experience with a literacy agent regarding her new book set in Swaziland. “An agent said to me, it is ok for a British person to write about England or the Caribbean and if you're Black African you can write about Africa, but nobody's interested in Black British people who write about Africa. She said you need to set the book on another continent because Black people have either got to have come from Africa to write about it and she dropped me for that reason”.

Writers of colour are under a literary banner, distancing them from the mainstream to appease the majority audience and the perception of what they will be interested in reading.

The White Gaze

Author Laura Fish continued “In publishing, there is an expectation that if you are Black you will write about certain things”.

Not only are authors pigeonholed and othered, but they also feel the consequences and conformity of the white gaze. The feeling of having to confirm or answer to the white gaze usually includes writing about race, colonialism and postcolonialism, aimed for and around a white audience. The foundational assumption is that the reader is someone who only identifies as white and the POC writer is required to substantiate their writing making an allowance for the reaction of a white reader. In other words, as the infamous saying goes ‘if it ain’t white, it ain’t right’.

Commissioner for 2015 Writing the Future report, Eva Lewin says how’s it’s “A shocking inability to kind of think beyond a white experience and a white readership, clearly, if that is not changing then the output of the publishing industry isn’t going to change much either” she continued, “We are a diverse society. The stories we tell ourselves and the discussions we have, need to be represented”.

In 1948, philosopher and author, Jean-Paul Sartre wrote a book called Black Orpheus, which expressed that through the European mindset of reasoning and rationale, the Black body is subjected to oppression, it is ‘the privilege of seeing without being seen'. In 1989, Samir Amin, a Marxian economist wrote a book called Eurocentrism, which explained what it is like viewing history within the prism of white voices and eyes. The concept of the white gaze is something implanted within the background and history of publishing.

Toni Morrison openly shunned this throughout fifty years of her writing career, in an interview with the Guardian, she says how she rejects the white gaze. “I’m writing for Black people in the same way that Tolstoy was not writing for me, a 14-year-old coloured girl from Lorain, Ohio. I don’t have to apologise or consider myself limited because I don’t [write about or for white people] — which is not true, there are lots of white people in my books. The point is not having the white critic sit on your shoulder and approve it” Literacy symbols such as James Baldwin and Toni Morrison conjured up the term to combat the one-dimensional narrative portrayed about Black Americans.

Perpetuating a dangerous account of a particular sort of group over centuries will undoubtedly influence ways of thinking. Making the targets more aware or be inclined to police their actions and decisions in order not to be portrayed in a particular light or seen in a very specific way. The white gaze is predetermined, omnipresent and unavoidable, it influences many if not all individuals. Since whiteness is seen as the norm, everything outside of this can be deemed aberrant unless it is connected to the gaze. For instance, Black and Asian and ethnic minorities books only being recognised in relation to race.

Sources: British Heritage, National Archives, BBC, South London Press, The Guardian and The Telegraph

Sources: British Heritage, National Archives, BBC, South London Press, The Guardian and The Telegraph

Snippet from the interview with Victor Headley

Every Twenty Years

In the late 1990s and early 2000s, there was a wave of commercialised successful black authors permeating the UK market. Malorie Blackman, Zadie Smith, Bernardine Evaristo and Dorothy Koomson all rose to fame on books based on fictional literacy. At the time, this was greeted with open arms, but the novelty did not last long.

Malorie Blackman recalls how liberating it felt to identify other writers that looked like her, she told Writing the Future in 2015 ‘For the first few years of being published I was always the sole face of colour at any publishing event I went to. About 10 years ago that changed and there were several faces of colour at various events. It was wonderful. Progress was finally being made’. This changed, Malorie started to see the emptiness of Black authors at these events ‘Over the last three or four years, I seem to have gone back to being the sole face of colour at literary or publishing events.

There is a cyclical performative routine of promoting the works of ethnic minority authors followed by industrial silence. In the late 1940s, after the second world war, Britain entered decolonisation due to colonial and ex-colonial mass migration and their demographic permanently changed. This was down to the influx of Caribbean emigrants who settled down in the country resulting in an increase of books by ethnic minority authors.

Between the 1950s and 1970s novels like The Lonely Londoners by Sam Selvon and In the Castle of My Skin by George Lamming were published, alongside more than 80 other novels by Caribbean authors. Selvon’s success partially derived from his novels based on the colonial experience. This spike did not last, the government implemented tighter immigration controls later leading to fewer people emigrating to Britain and ultimately fewer opportunities. Interest then shifted to West African authors, particularly of Nigerian descent such as Chinua Achebe and Wole Soyinka. In the 1960s, the British empire was declining with many African countries going through the process of decolonisation and gaining independence.

Twenty years later, another peak happened in a response to a series of uprisings. In 1980s, 13 Black young adults were killed in the New Cross Fire, which led to protests and marches on how the police handled the investigation, and the discontent culminated in Brixton Riots which was a response to violent policing. Author Alex Wheatle wrote a book surrounding the Brixton Riots which was later published.

In the early 1990s, Xpress; a Black-owned publisher founded by Dotun Adebayo, and Steve Pope published Victor Headley's Yardie. It was the first number one bestseller by a Black British author, Victor expresses the efforts for the book to become popular “I was working for The Voice, freelance at the time and I knew had no other choice but to self-publish. So, we (Dotun, Steve and Victor) all put £500 pounds each to print 3,000 copies and posters. I personally went and put it in barbershops in London – and that is when it picked up” its success prompted WHSmith to set up Black book sections in their stores. Victor Headley recalls the reaction of the press to his bestselling book “After that it got more popular, I was interviewed by a lot of journalists who tried to label me as a reformed gangster, which I was not, I wasn’t a gangster just an ordinary man writing a story. I think because they thought it would sell more.”

Fast forward to the early 2000s, when the new millennium began, the term “multicultural” was recycled and repeatedly used to describe Britain’s changing face. Writers such as Zadie Smith, Monica Ali and Diana Evans rose to fame. Diana expressed what the label multiculturalism meant to her, “It was a label I didn't feel comfortable with. It implied, I was a mouthpiece for anything to do with race and multiculturalism in Britain”.

In June 2020, another boom started after the death of George Floyd, an unarmed Black man who was murder by the police in Minneapolis. His death resulted in worldwide protest leading to an interest in Black, Asian and ethnic minorities stories.

Countless publications, bookstores and social media platforms released recommendations of books for the general public to educate themselves and indulge in. It is questionable whether this wave will be a herald of a permanent change. Based on previously set precedents from the past and considering how the current wave of inclusion was solely triggered by a reaction to a tragic event, it is easy to see how one might be thoroughly discouraged.

This twenty-year cycle could betray the tokenism at the heart of the intent of the industry’s promotion of their selected authors. Tokenism stands as the façade under which the established hierarchy appears to operate in the interests of disadvantaged groups while exerting the minimal possible effort to maintain this appearance. It appears as promoting and publishing a small number of marginalised groups work sporadically or conveniently. When it comes to the workforce, this appears as recruiting some individuals from the minority in order to portray a display of equality.

The endless publications of books and lists on reading against racism do not accurately represent the internal landscape of the publishing industry.

In February 2021, Publishers Association conducted a survey which determined out of 14,122 employees over 71 different publishing companies, around 13% of the workers were from Black, Asian and minority ethnic groups. The percentage of minority employees has remained the same since 2017, yet the number of employees has risen. This is a considerably low number because most of the publishing companies are based in London, where 40% of the population is of ethnic minority descent.