The Pursuit of Happiness: Do we know when we're happy?

In 2020, MIND reported that 1 in 4 people living in the UK suffered from a mental health disorder. So why are so many people unhappy, and what makes us happy?

Thanks to the advancement of technology and the invention of social media, it’s more accessible than ever to educate yourself on mental health and to get help if you need it. With so much information on mental health issues readily available, I wanted to research phrases like ‘happiness’ and ‘am I happy?’ to see how much information is available to us in contrast. However, when assessing the results, nothing properly explained what happiness should feel like. The first search result that appears when you search for ‘happiness’ on Google is a quiz called ‘Happiness quiz: How happy are you?’; the quiz was made with the intention of telling users how happy they are, based on their responses.

Aside from the multitude of quizzes that make up the majority of search results, there doesn’t seem to be enough useful information on happiness. It became apparent to me that people don't know when they feel happy, and consequently go to Google in the hopes that they'll find the answer there.

Interestingly, when you search the word ‘unhappy' in Google, the first result is the Oxford definition of the word, followed by an abundance of information on mental health. The Oxford Dictionary defines the term 'unhappy' as sad or not satisfied. In contrast, the Oxford definition of the word 'happy' is feeling, showing, or causing pleasure or satisfaction.

Between 1993 and 2014, there was a 20% increase in the number of people suffering from mental health problems, with the percentage of people reporting severe mental health symptoms reported each week increasing from 7% to 9% or more.

Notably, the people most affected by mental health problems in the UK are those from the LGBT+ community, people aged between 16 and 24, and black or black British people. In 2019, 23% of people falling into any of these three categories experienced mental health problems in any given week.

With mental health problems on the rise, it was no surprise to see that a survey conducted between April 2019 and March 2020 by the ONS revealed that levels of happiness had fallen by 1.1%.

Lockdown and the pandemic has changed almost everything about our lives. People can no longer socialise in the way they once did, and we are all limited in our in-person social interactions. Between April and June in 2020, personal wellbeing significantly worsened, with life satisfaction falling by 1.8% and levels of anxiety rising by 4.8%.

In April 2021, after analysing the most up-to-date ONS report, The Royal College of Psychiatrists reported that there had been an increase of 80,226 people aged under 18 being referred to mental health services compared to the previous year.

Based on the data found on happiness and mental health in the UK, it's clear that the mental wellbeing of people has steadily been on the decline. This raises the following questions: Why is this happening? Do we understand what it means to be happy? And could more education on the subject help people?

This piece will explore the different theories of happiness and investigate how accurate they are through data analysing, vox pops and interviews, all with the mission to discover, do we know what makes us happy and people's understanding of happiness.

Bruce Hood is a Professor of Development Psychology in Society, specialising in the Science of Happiness at Bristol University.

Bruce has long researched happiness and the science of what makes us happy. He is best known for his books SuperSense: Why We Believe in the Unbelievable and The Self Illusion: How the Social Brain Creates Identity, where he discusses his theories on happiness. More recently, Bruce has released a study called 'The benefits of a psychoeducational happiness course on university student mental well-being both before and during a COVID-19 lockdown'. In the study, he taught students about the different theories of happiness and provided them with strategies to help them improve their mental wellbeing.

Bruce further speaks about mental health in the above interview. He discusses whether or not we know when we’re happy and reflects on the education system, speaking on how implementing lessons on happiness could prove to be highly beneficial for students and their general wellbeing.

I feel that, as humans, we only ever focus on the bad things in life. We often fail to see the bigger picture, and tend to be unable to recognise when we're happy in the moment.

If there was more education on happiness, I think we'd all be happier. I hope that by reading this, at least one person will walk away with a better understanding of happiness, and will ask themselves: Do I know when I'm happy?

Popular Theories of Happiness

One of the most popular theories of happiness originates from Japan, and is known as Ikigai. Ikigai means ‘a reason for being’, and works under the belief that having direction and purpose in life will achieve happiness. Ikigai is made up of four components: passion, vocation, profession and mission. The concept teaches us that happiness comes from discovering what you love, what the world needs, what you can get paid for and what you are good at.

Another practised theory on happiness is Hedonism. The central belief of hedonists is to live your life experiencing pleasure and avoiding pain. Hedonists see happiness as a raw subject feeling and seek to find it through instantaneous pleasure. A happy life is filled with as much joy as possible.

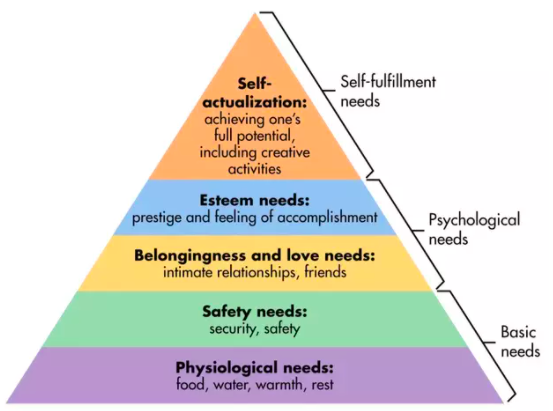

One notable theorist that studied happiness is Abraham Maslow, who hypothesised that we need to follow the hierarchy of needs in order to be happy. The pyramid shows that to be satisfied in life, we must first fulfil our basic needs of feeling safe and having food, water, rest and warmth. The next level to the pyramid is psychological needs. This consists of esteem needs and the need to feel like we belong, characterised by intimate relationships and friendships. At the top of the pyramid lies self-actualisation. This layer is about self-fulfilment and focuses on the need to fulfil our potential in order to be truly happy.

Source: simplypsychology

Source: simplypsychology

Views on Happiness

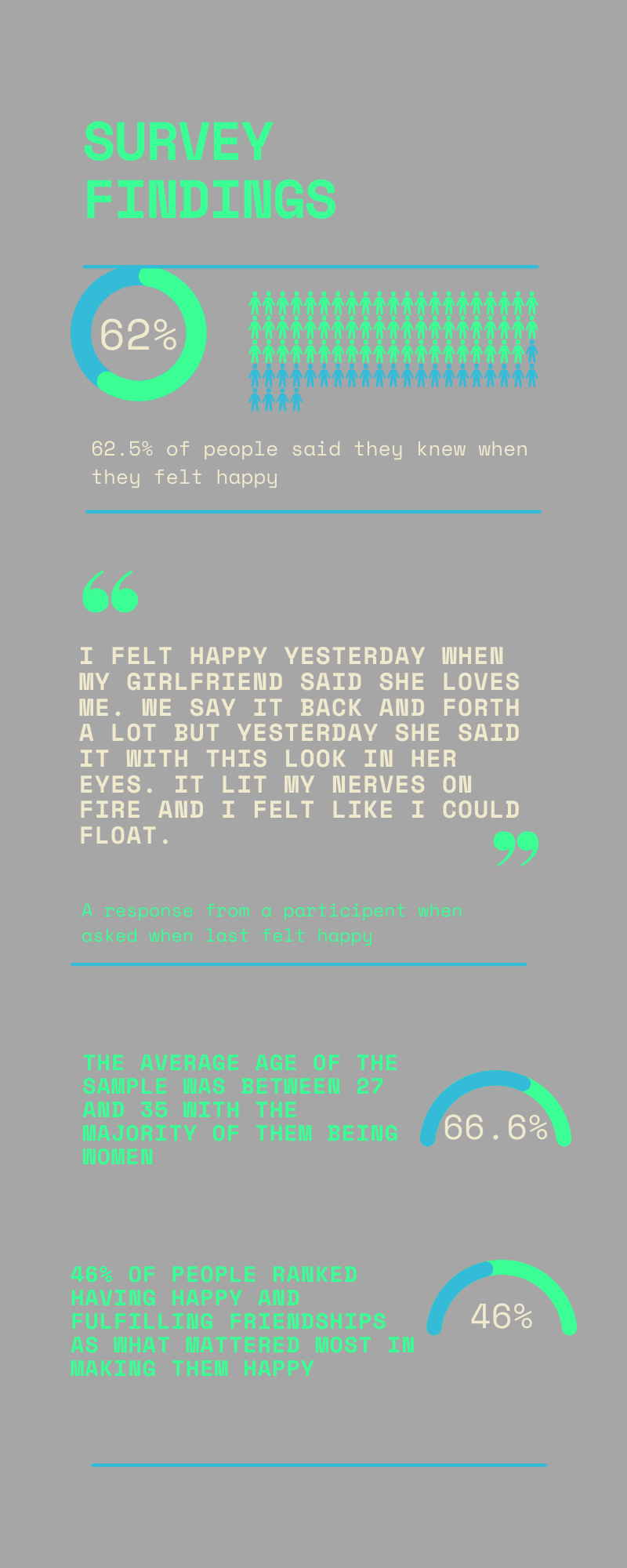

Researching further into people's views on happiness, a survey was handed out and completed by 250 participants. The survey found that around 62.5% of people felt they knew when they were happy, with the remaining 37.5% saying they felt unsure.

The findings from the survey indicate that most people seemed to understand when they felt happy and could recall times they felt comfortable. The candidates in the sample valued having happy and fulfilling friendships and romantic relationships above all. In second and third place was having money and having a fulfilling career respectively. These findings support the theory of IKIGAI, in that participants find happiness in doing something they love and feel passionate about.

The next method of research came in the form of a vox pop. Participants were asked the question: What makes you happy?

The things that make people happy vary so much from person to person. Variables such as age, gender, religion and cultural differences mean that we all experience happiness differently. Based on the vox pop, it seems the participants were able to identify if they knew when they were happy, and were able to detail what made them happy. It's surprising that all participants were able to identify what made them happy, considering the significant decline in levels of happiness in recent years. If people know what makes them happy, what's stopping them?

Rates of mental health disorders have steadily been on the climb amongst children since 2017, with 1 in 6 children aged between 5 and 16 being identified as having a probable mental illness in 2021, compared to 1 in 9 in 2017.

Interestingly, in 2020 the ONS surveyed children's views on wellbeing and what makes a happy life. The main findings are that children prioritized having good relationships with people in order to have a happy life.

Evie

Evie speaks about what happiness means to her, how her perspective on happiness is different to someone else and the last time she was happy.

In a survey completed by the NHS, similarly to the aforementioned statistics on children, the number of young people aged between 17 and 22 suffering from mental health problems also increased between 2017 and 2020. The data showed that women were far more likely to suffer a mental health disorder in comparison to men, with 27.2% of women and 13.3% of men being identified as having a probable mental health disorder.

Isabella

Isabella is a 22-year-old who suffers from Borderline Personality Disorder. BPD is a mental health disorder that profoundly affects how people think and feel. Classic symptoms of the condition include fear of abandonment, being emotionally unstable, acting without thinking and having upsetting thoughts. BPD mainly affects people's emotions and has a significant impact on their mental wellbeing. Isabella explains how having BPD impacts her perspective on happiness.

What does the word happiness mean to you?

"The word happiness had meant different things to me throughout my life; when my BPD was untreated, I identified happiness as a euphoric, manic state that almost felt like despairing at points, and I saw happiness as this suburban comfort in others."

Do you think that you always know when you feel happy?

"I think for me happiness is mainly felt through my bodily sensations, and I usually get a feeling of warm energy spreading over me when I feel good, and because I suffer from intrusive thoughts, I'm not able to always trust my thoughts as identifiers for my emotions as they can mislead me."

When was the last time you felt happy?

"The last time I felt happy was probably a few nights ago when I was driving in my friend's car late at night, and sometimes we drive through the back lanes super fast and blast music we both like. I felt very free in that moment which I view as happiness."

Do you think BPD affects how happy you feel?

"BPD 100% affects how happy I feel. In too many ways to explain, but some of them are that I always feel like an intruder in my own body, so I don't trust my thoughts and emotions. Secondly, I suffer (not as much nowadays) from turbulent emotions, so one hour I might feel like the most joyous woman in the world, and the next I'll be on edge crying my eyes out."

Do you think you view happiness differently from someone that doesn't have BPD?

"I feel like that consistent "contentment" that the majority aspire to/possess is more unrealistic for me. I also feel like other people may or may not base happiness on achievements in their lifetimes, such as having a family or getting married. In contrast, I know that my idea of happiness will only be truly reachable when I can stop meeting the BPD criteria through therapy and self-work."

Has your outlook on happiness changed because of the pandemic?

"The pandemic hasn't affected me too much because I was already going through a really painful time when it began. If I'm honest, I almost felt grateful when it first happened because it felt like a break from the world. If anything, I'm pretty nervous about returning to the 'real world'."

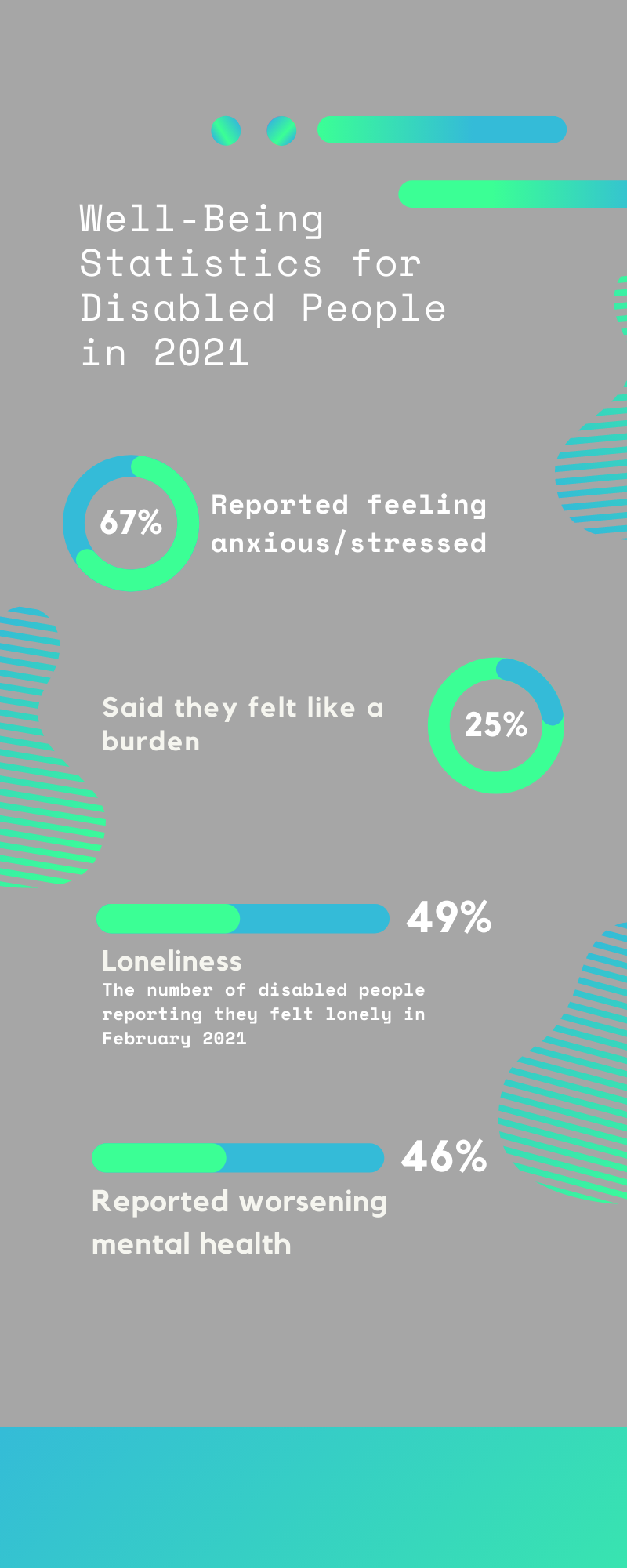

Coronavirus and the social impacts on disabled people in 2021 in the UK, a study conducted by the ONS, found that the mental wellbeing of disabled people had drastically declined since the pandemic had begun. The survey found that disabled people had lower wellbeing ratings than non-disabled people. These ratings were measured by factors such as life satisfaction, feeling that things done in life are worthwhile, happiness and anxiety.

Source: ONS

Ewan

Ewan is a 23-year-old who was recently diagnosed with autism. He speaks about what the word 'happiness' means to him, how living with autism has impacted his life, and how he interprets happiness differently to others. He also speaks on the impact of the pandemic and how it has changed his life for the better.

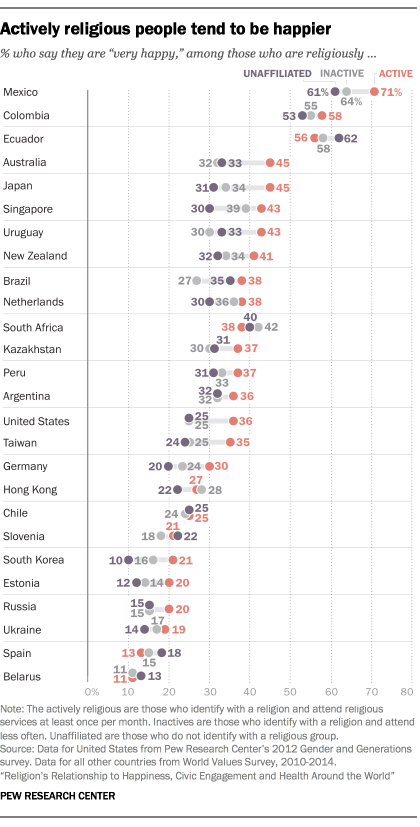

Religion can play a significant role in people's happiness. Reports from The Pew Research Center suggest that 36% of people who followed a religion were living happy lives, compared to 25% of non-religious people.

Source: Pew Research Center

Katie

Katie was raised Catholic and converted to Islam aged 19. She became a Muslim after meeting her now-husband, and the couple have raised three children, who also practice Islam. She shares her unique thoughts on happiness and what makes her happy.

In a paper written by David G. Blanchflower, it is suggested that, around age 47, there is a period where the happiness of individuals tends to dip. However, in the years after 47, levels of happiness supposedly rise. The research he conducted found that the main reasons older people were happier were that they were more trusting, more financially stable, and found happiness in the smaller things in life.

Carol

Carol, aged 69, speaks about what makes her happy, how what makes her happy has changed over the last few years, and how the pandemic has changed the way she views happiness.

What does the word happiness mean to you?

"Happiness to me means freedom from problems and niggling worries. And peace - learning not to worry about what you can't change and focus on what you can, in a positive way."

Do you think that you always know when you feel happy?

"I don't always know when I feel happy, and I just get a sudden realisation that I feel "lighter" so I know I am happy for the moment."

When was the last time you felt happy?

"I'm not sure the last time I felt happy, although I don't feel unhappy. Laughing and chatting with people in shops makes me feel cheerful. Something trivial like a friendly few words and a smile, like yesterday when I went to TK Maxx, makes me feel fairly happy."

Do you think what makes you happy has changed over the years?

"What makes me happy has definitely changed over the years. Happiness to me now is knowing my family is okay. There is less emphasis on being happy about your appearance and more on health and security. Happiness now is less about my personal feelings and more if someone in my family has had something good happen to them (reflected happiness)."

Do you think older people view happiness differently from the younger generation?

"I think some older people appreciate happiness more than younger people because they know how fleeting it can be. Older people get happiness from looking at plants, flowers and nature because they have time to do so. Younger people generally are busier and have lots more to focus on, so sometimes they take happiness for granted. Older people appreciate happiness from little everyday things. All generations can get happiness from their favourite music."

Has your outlook on happiness changed because of the pandemic?

"My outlook on happiness personally has not changed much because of the pandemic other than increased worry for the future of humankind. Not being able to mix with family is sad, but I feel happy that we have good channels of communication and can keep in touch 24/7."

The Future

The future of happiness could seem bleak to some, with the number of people suffering from mental health problems in the UK expected to rise continuously for the next few years.

The pandemic has meant that, statistically, mental health problems are the most common that they've been in ten years, levels of happiness have gone down, and levels of anxiety and depression have risen.

The Royal College of Psychiatrists predicts that this is only the beginning, and that mental wellbeing will continue to decline. In comments made to the Guardian, they said: "The extent of the mental health crisis is terrifying, but it will likely get a lot worse before it gets better. Services are at a very real risk of being overrun by the sheer volume of people needing help.”

Some argue that the future of happiness looks positive. Laurie Renee Santos, a cognitive scientist and Professor of Psychology at Yale University, introduced a project called The Science of Well-Being, which was then picked up by Bruce Hood and delivered at Bristol University.

Accredited courses on happiness were offered to students in their first year of study. There were almost 1000 students that took part in the study, who were taught how the brain works as well as practises to achieve a happier, more fulfilling life. The course also revealed the effects of loneliness on the brain and how it impacts the physical body, and contrasts the impact of optimism on our life expectancy. After taking part in the course, students reported to the Guardian:

Laurie explains why she thinks people can live better lives when educated on happiness, as well as her thoughts on what the future holds for happiness.