Complex Regional Pain Syndrome

It's all in your head

Imagine the feeling of a loved one brushing their hand against your leg.

Perhaps you needed comforting after an awful day at work, or maybe simple intimacy.

Now think of this loving hand wrapped in sandpaper, scraping and scratching it’s way across your skin.

Can you remember the last time it rained?

Not just a drizzle.

Picture the last time the heavens truly opened and you were caught in a downpour. Think about the feeling of the rain against your flesh. The pleasant smell of petrichor.

Imagine gentle drops of water turning into thousands of icepicks, slicing through your limbs and perforating your bones.

Burning hot, sharp stabbing pains.

Feelings of your arm being placed in a vat of boiling oil, changing suddenly to bitterly, ice cold water.

Imagine severe swelling of your legs, being unable to walk, experiencing complete hair loss on parts of your body and in those same areas rapid unexplained hair growth.

Your skin is hypersensitive to the lightest of touch, bed sheets induce searing agony and your long list of painkillers provide little to no relief for any of these cruel sensations.

There is no respite at bedtime, because you cannot sleep.

The pain is at it’s worst when your mind should be switching off.

Instead, you are writhing and tormented, physically and mentally exhausted.

What you have just tried to envision is the reality for sufferers of a rare, debilitating illness known as Complex Regional Pain Syndrome.

There are around 14,000 diagnoses of CRPS every year in the UK, and there is no cure.

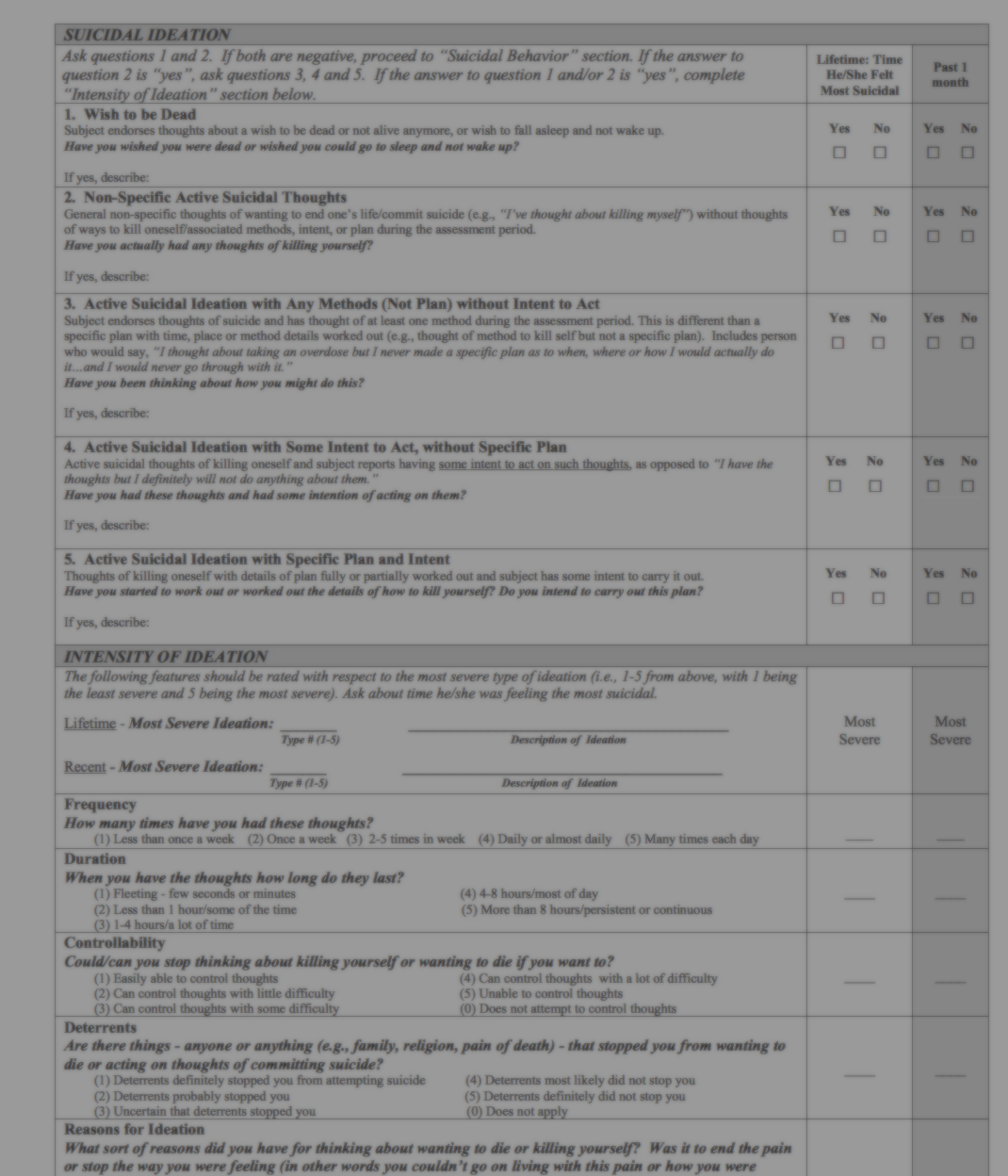

Dubbed the suicide disease, studies have found significant numbers of sufferers to report suicidal thoughts, with around 20% of those with the illness attempting to take their own life.

The exact number of people who kill themselves as a result of their pain is unclear, but estimates are high in comparison to other chronic illnesses.

Recently, there has been an attempt to move away from this "suicide disease" phrasing, which Warriors argue "paves the way for hopelessness and desolation".

People within the CRPS community often label themselves as Warriors rather than sufferers, to more accurately describe a daily battle which they have no choice but to fight.

“It’s a condition that won’t kill you, and that’s the bad news.”

- Writes James Doulgeris in his blog post, titled “CRPS, a new four letter word from hell.”

CRPS can spread to other limbs, and there is a small percentage of people living with this illness who have CRPS throughout their entire bodies.

James falls into this category. He contributes to a blog for people in the US who live with the illness.

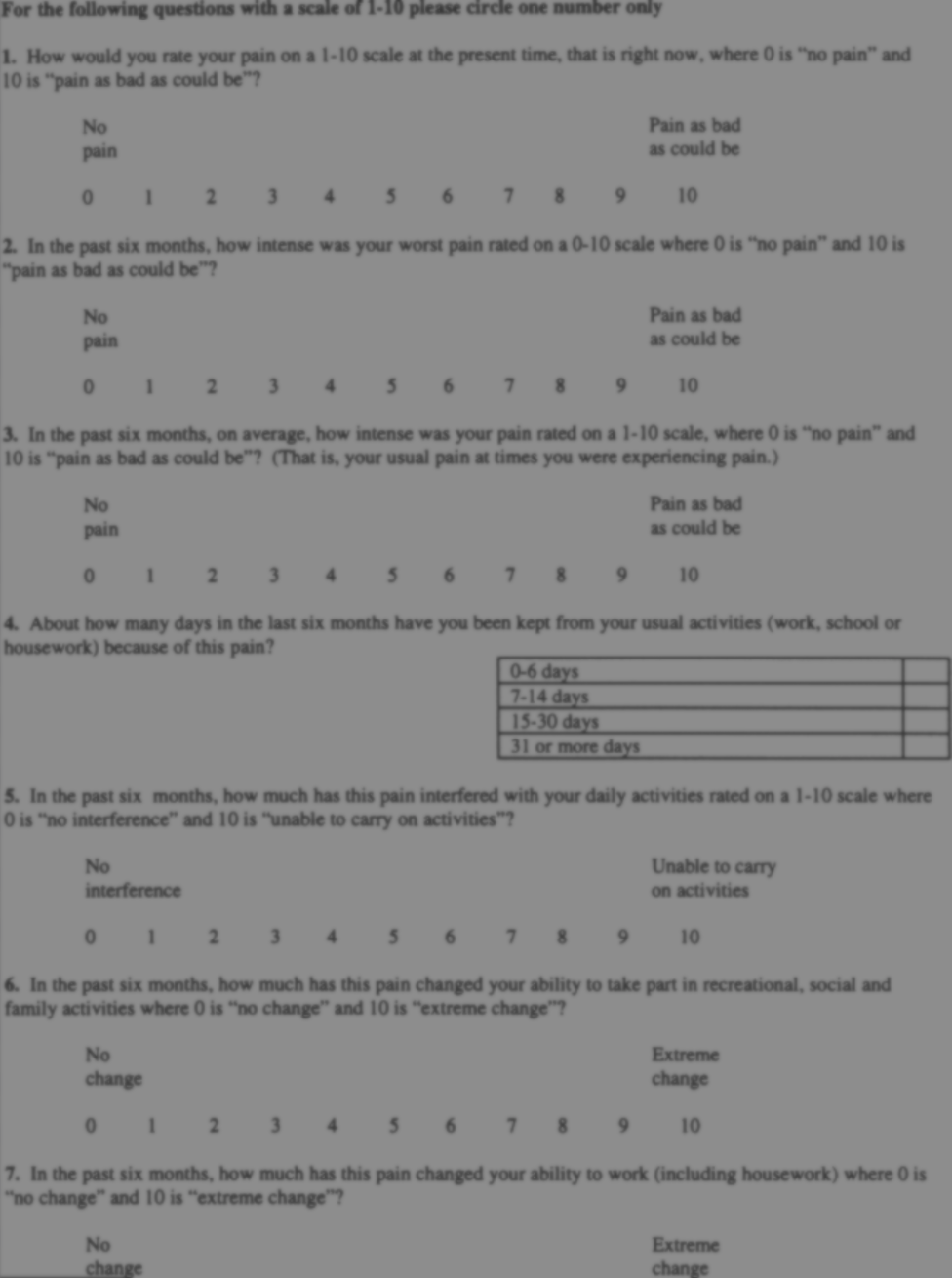

CRPS is the highest ranking pain disorder on a scoring system known as the McGill Pain Index, sitting at 42 out of 50. A chronic illness (lasting longer than 6 months), people usually live the rest of their lives in pain after their diagnosis.

In many occasions, this happens because patients are not diagnosed soon enough. The disease disguises itself as no more than psychological in nature, averting the objectivity of diagnostic tests like MRI’s, X-Ray’s and CAT scans.

Once CRPS has slipped through the cracks, it plays tricks on the uninformed GP, settling in with ease after the 6 month window of opportunity passes, and chances of remission or recovery begin to dwindle.

The majority of medical schools fail to offer much in the way of courses dedicated solely to pain.

One study found this to be the case for 96% of courses in the UK and the USA, with 80% of medical schools in Europe lacking any compulsory pain curriculum.

Because of these bleak numbers, a large proportion of people with this illness have had their sanity questioned by a GP.

This response by doctors is in no way reflective of the UK Strategy For Rare Diseases, which promises to make sure not a soul is left behind just because they have an illness that affects a very small portion of the population.

Despite huge progress in the last decade on the understanding of CRPS, many of these people are still falling victim to our healthcare systems.

![[object Object]](./assets/jVcfRkN0Of/mcgill-750x794.jpeg)

Pain scale adaptation by Burning Nights

Pain scale adaptation by Burning Nights

![[object Object]](./assets/0GZvEPx8lq/28ff1-881x1197.png)

What exactly is CRPS?

CRPS is characterised by intense pain attacks in parts of the body, usually after some form of physical trauma, such as surgery, or a fracture.

Swelling of the limb, changes to skin temperature, texture and colour are all symptoms of CRPS. All of these symptoms are accompanied by extreme pain.

People with CRPS may experience abnormal sweating, as well as rapid hair and nail growth of the affected limb.

Sufferers often report their limb to feel foreign, as though it does not belong to their body.

This disease does not live in fear of therapeutic intervention.

Especially not early on. Nor is it wary of qualified medical staff equipped with sound knowledge on how to tackle it - this is because analgesic experts are few and far between, and are not stumbled upon by chance.

Even the researchers who have studied the disease for many years do not understand it’s precise mechanisms, which means the circle of medical experts who are aware the illness exists, is kept small. Consultants who are willing to take on a patient with an illness like CRPS are a rarity, and it takes many rounds with a GP before a referral is made.

Those with the illness describe a shooting, burning, stinging sensation of the same pain severity as childbirth free from anaesthesia, and natural amputation. When compared with childbirth, the pain from CRPS does not stop as it would after the end of labour and the birth of a baby. This comparison is used to show the magnitude of permanent, unrelenting agony that can remain for weeks in a flare up of CRPS symptoms.

Maxine's case of CRPS was unusual, destroying the bone marrow in her foot.

Maxine's case of CRPS was unusual, destroying the bone marrow in her foot.

The illness does not discriminate against race or age, but has a three to four fold higher preference for females, according to research on CRPS risk factors. It can take several years for patients to end up in the office of a doctor who knows, cares, and is educated enough about the condition to give them a firm diagnosis.

Contrary to what one might think, for many patients their diagnosis is a beacon of hope. Especially for those who were misdiagnosed, Like Helena, who lives in the US.

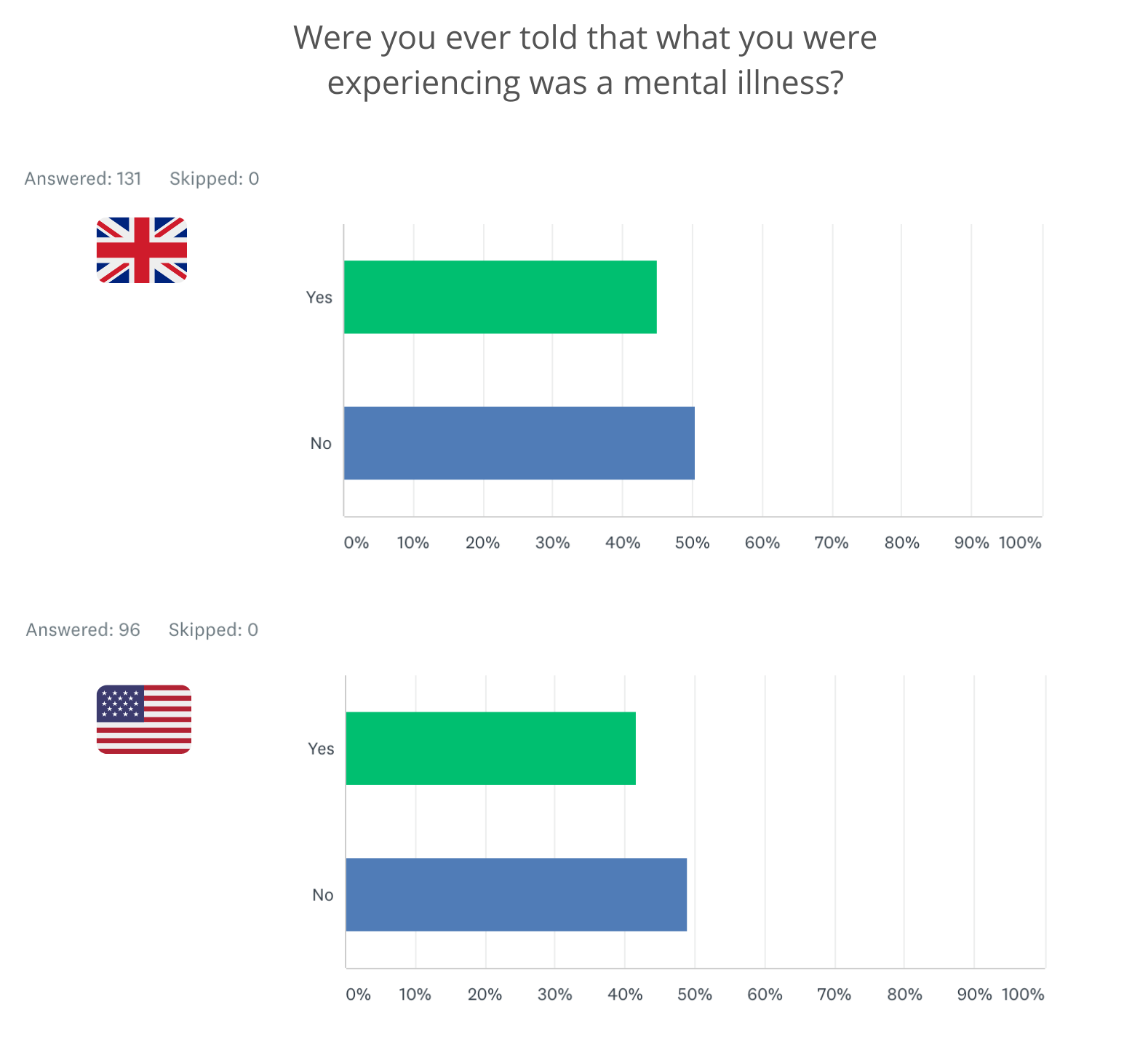

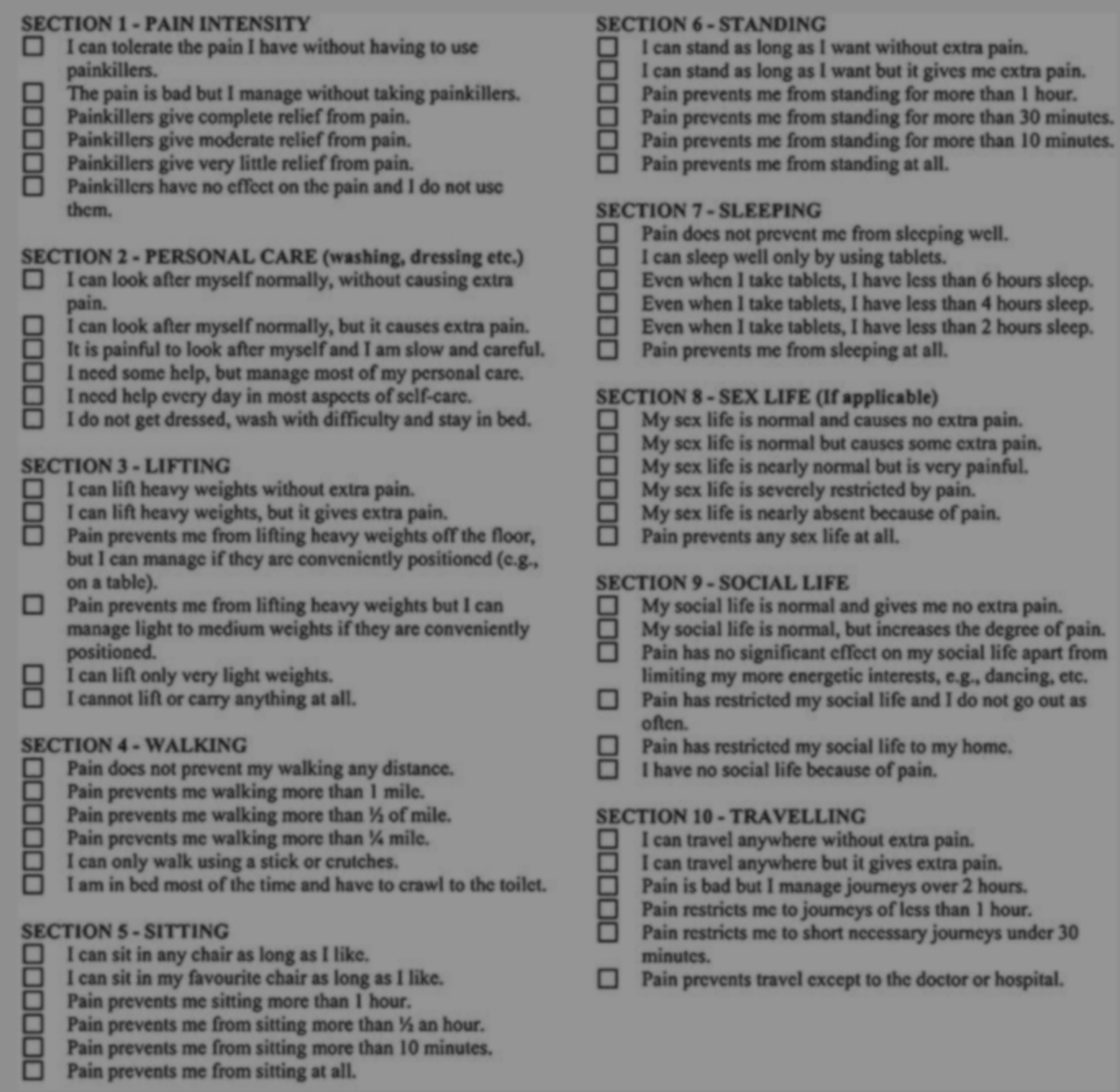

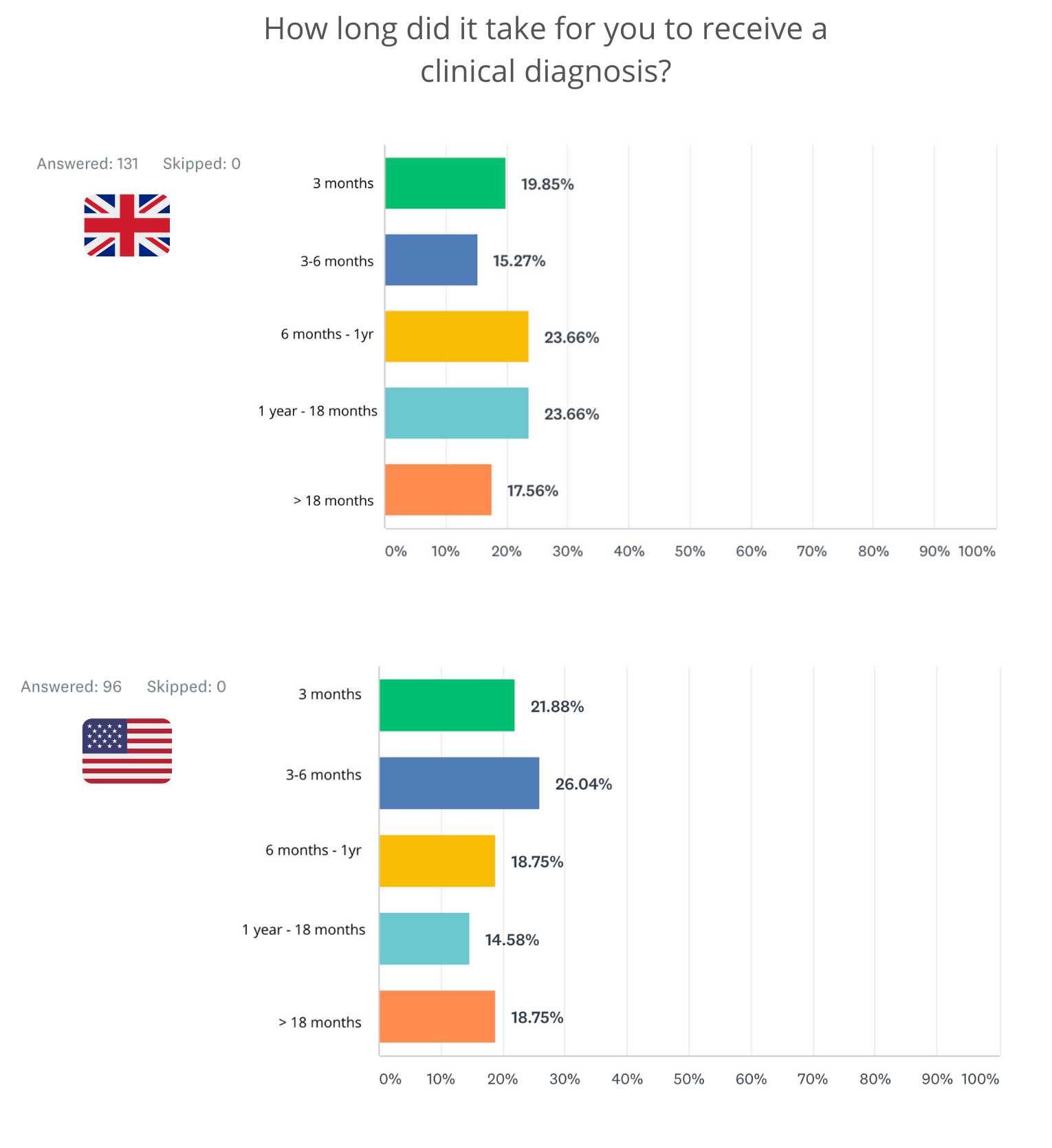

Along with 96 other CRPS patients from America, Helena completed a survey answering questions about her diagnosis process and aftercare, which was distributed via social media by one of only two CRPS charities in the UK, Burning Nights.

A second identical survey targeting CRPS patients in the UK was distributed across the same social media channels, receiving 131 respondents.

Although these survey responses are anecdotal, very little difference can be seen between the answers of these focus groups, implying the issues surrounding the illness are commonplace, irrespective of which part of the world you live in.

Helena received many incorrect diagnoses.

“Before my diagnosis of CRPS, I was told I had generalised chronic pain, tendinitis, anterior cruciate ligament tears, and psychological issues. It took me 12 years to receive a diagnosis of CRPS. I was then referred to a specialist within 2 weeks.”

For many, a diagnosis helps to unravel what was once unexplainable, and facilitates the beginning of a journey to recovery from a physical illness they are told does not exist beyond the parameters of their psyche.

But do not be fooled - CRPS is far more than a mental disorder.

Why is the type of pain associated with CRPS different?

The belief held by science is that pain as we know it tends to fall under two categories - nociceptive and neuropathic. The former is the most common type of pain we experience, usually from physical damage to the body, whilst the latter is more complex and involves the nervous system.

These differences are addressed in the biopsychosocial model of pain, first proposed in 1977 by George Engel and John Romano in the journal Science. Both physicians were fed up with the lack of emphasis on the differing experiences of chronic pain patients who in their view, rarely had their life events taken into account.

Engel stressed that responses to pain were “sculpted by complex and dynamic interactions of biological, psychological and sociocultural factors” and were not strictly biomedical in nature.

Several studies have looked at the implications of stressful life events and to what extent they occur in patients with Complex Regional Pain Syndrome, with some identifying a correlation. This is however only one of many potential influencing factors, with no one able to say with certainty which are the most important.

Neuropathic pain involves damage to our nervous system, usually due to disease or injury. While experts are yet to collectively agree on the exact mechanisms of CRPS, they are all in agreement of the illness being neuropathic, with CRPS said to involve the sympathetic nervous system more than other kind of neuropathic disorder.

When you stub your toe, it hurts. You may scream an expletive (a scientifically proven way to help alleviate this type of pain, summed up nicely in this Wired article ), ball up your first or bite your bottom lip. These responses are reactions to a physical trauma that has triggered a flood of neural signalling.

Research has shown a great deal to happen in those moments. The blunt force impact strikes nerve receptors on either side of your toe, with these signals integrating in your spinal cord, relaying that information to your brain via sensory neurons called nociceptors.

Nociceptors pick up on external stimuli that could potentially harm the body, and are on the hunt for three different types: Extreme heat or cold, chemicals which could damage or burn the skin, or mechanical pressure.

In this case, nociceptors have responded to the mechanical pressure of the force applied when banging your toe into a hard object.

Once all of this information has been processed by your brain, you perceive it as pain, which then disappears in a few moments depending on how hard the hit.

If CRPS were to develop after blunt force trauma, something has gone haywire with neuronal signalling and instead, extreme pain that is disproportionate to the initial injury will persist, even when all signs of the inciting event no longer exist. It may even spread to a person's entire leg, which has been documented, although rare.

But why would a surgery or injury lead to CRPS, when it wouldn’t lead to CRPS in another person who experienced the same trauma?

Genetics are thought to play a role in the onset of the disease, and there is some evidence to suggest a correlation between stressful life events before the triggering incident. However, most studies show no link between CRPS and any psychological disorders such as depression, anxiety or paranoia. These disorders do end up manifesting alongside the disease, but they have not been proven to be prerequisite to CRPS.

According to research presented in the British Journal of Anasthesia, inflammation is the most prominent mechanism of action in terms of disease onset, but scientists remain perplexed at the pathophysiology of CRPS and academics are yet to agree on this.

One way to understand CRPS is by thinking of an allergic reaction. In allergies, some people may respond excessively to a trigger which otherwise causes no problems for others.

It is thought that one single cause of CRPS is unlikely, and it is more probable there are many influencing factors that lead to it’s onset.

What does CRPS feel like?

Maxine Tripp lives in Wyoming, and was diagnosed with CRPS after an accident at work. The disease destroyed the bone marrow in her foot, which is an incredibly rare complication that her care team did not know could happen.

Key characteristics of CRPS are colour changes, temperature changes and skin that is weakened with a susceptibility to split open, amongst other things.

This is a problem Maxine is currently dealing with - her ankle has been split open for a quite some time.

To combat this, Maxine is seriously considering amputation.

Ulceration is also incredibly common, and many patients are accused of self harming due to wounds that refuse to heal.

Victoria Fleming is the founder of the CRPS charity Burning Nights. She was called to the bar as a barrister, and had a bright future ahead of her when a minor accident led to the development of CRPS.

Since becoming ill, Victoria has dedicated her life to the charity ran entirely by volunteers, many of whom have CRPS.

The following images are graphic, so please scroll further down if you would prefer not to see them.

Victoria has since had her other leg amputated, and is now a bilateral above knee amputee. Amputation is a controversial treatment for CRPS, as it can potentially aggravate symptoms.

Victoria has since had her other leg amputated, and is now a bilateral above knee amputee. Amputation is a controversial treatment for CRPS, as it can potentially aggravate symptoms.

Victoria's skin had gone from a "wet soggy mess" to blistered, dry and cracked. Pain consultants said they could no longer help her, as she was "too complex a case, too far down the line and too extreme".

Victoria's skin had gone from a "wet soggy mess" to blistered, dry and cracked. Pain consultants said they could no longer help her, as she was "too complex a case, too far down the line and too extreme".

The name of the charity Burning Nights Is an amalgam of the two most defining attributes of Complex Regional Pain Syndrome - Burning hot pain, which is worse at night.

CRPS UK is another charity founded and manned by those with the illness, who’s co-founder Sue Pendragon says the most accurate way of describing the pain of CRPS to a person who has never heard of the condition before, is by likening it to “electric shocks, to being in a freezer, then into a hot oven.”

Gary Carnell volunteers for the same charity, and has similar sensations. He was involved in a motorbike accident and broke both ankles, needing plates and pins to repair the bones. In total, Gary underwent nine surgeries, and has lived with CRPS for 7 years. He received his diagnosis of CRPS 5 years after his symptoms began.

“I would describe my pain as having both feet and ankles in a pan of boiling water, simmering away 24/7. This is the norm for me, but sometimes I feel other things, like cutting, spikes and needles.”

The people on Gary’s care team were so poorly educated on CRPS, not only was he made out to be a liar, he was treated with acupuncture and hot and cold therapy. These are among some of the most shunned treatments for a CRPS affected limb.

With injuries that lead to inflammation on an otherwise healthy body part, ice is recommended to bring down swelling, but in patients with CRPS, ice can cause symptoms to come on faster, and will lead to frost bite if left on for too long.

Some studies have reported the prolonged and repetitive application of ice to damage the myelinated motor and sensory nerves, sometimes leading to paralysis of damaged nerve fibres for up to one year.

Since many physicians do not know of CRPS, the desire to treat symptoms as though they belong to a healthy limb is common, but the skin of a CRPS affected limb is not anything like that of healthy flesh.

The impact of CRPS on mental wellbeing is unparalleled. The illness takes hold of every area of life, and the risk of suicide for someone with CRPS is incredibly high.

Gary’s mental health has been in decline for several years now. He says the illness has impacted his social life to such an extent that he has only one true friend.

“I don’t sleep, I’m exhausted all the time, I can’t work, I have no partner. My speech has slowed and is sometimes slurred. I’m existing, not living.”

Dr Petrina Ayerty-Gbeve is a clinical research physician and Principal Investigator of a CRPS clinical trial, for St Pancras Clinical Research.

Along with many others physicians who are aware of the disease, Petrina believes an earlier diagnosis is one of the best ways of improving the outcomes for patients.

Dr Petrina discusses medication, mental wellbeing and ways to improve the outcomes of CRPS patients.

Dr Petrina discusses medication, mental wellbeing and ways to improve the outcomes of CRPS patients.

What happens when an injury at work leads to CRPS?

Katie is an NHS worker who cares for vulnerable adults with disabilities, and has lived with CRPS for two years after being bitten by someone in her care.

Katie's GP asked her if she wished to increase her antidepressant dose, and told Katie she was suffering from a psychological illness despite her pain keeping her awake at night.

Luckily, Katie has been able to keep her job, but many people are left unable to work due to the disabling nature of CRPS. Maxine is one of them.

One way of staying afloat financially when unable to work, is by filing a claim for compensation against the person or employer who is responsible for the onset of the disease through their negligence.

Both Katie and Maxine were injured at work, but had very different outcomes due to the differences in laws that govern where they live. Maxine lives in Wyoming in the US, and her state laws protected her employer from direct legal action.

In the US, you must go through the Workers Compensation system for any type of financial assistance if you are injured at work.

Workers Comp provides medical and wage benefits to people who are injured in their place of work in the US, but this system does not allow for the same level of renumeration as people who bring personal injury claims against their employers in the UK, who can often receive 6 figures payouts if such claims are successful.

A survey respondent from the US described difficulty in receiving a CRPS diagnosis within this system.

“I live in Southwest, Colorado, 4-hours from a big city. Physical therapists call it CRPS & RSD (RSD stands for Reflex Sympathetic Dystrophy, an outdated term for CRPS), but the doctors are all afraid to diagnose CRPS in the workers compensation system.”

The Workers Comp system is designed to be "no fault". This means even if your employer was negligent, you are only entitled to receive limited medical benefits and payments, and you cannot sue your employer directly.

Katie was able to bring a legal claim against her employer, which means she can hopefully expect to receive some type of renumeration for the life changing accident which triggered her CRPS. This was no more than a bite, which would leave most people relatively unharmed, but Katie’s body reacted differently.

BLB Solicitors

Richard Lowes is a personal injury solicitor who works within a team of 6 injury litigation experts. Richard specialises in accidents resulting in CRPS, and has many years of experience in securing high payouts for his clients.

The amount of compensation a CRPS claimant can receive is usually quite substantial, reflecting the severity of the disease and the limit it places on quality of life and happiness.

Such high payouts are also reflective of the likelihood that this illness will be with Richard's client for many decades to come, and may very well spread to other parts of their body.

Many claimants start out with other firms, who don't understand the intricacies of the illness, with little to no access to CRPS medical experts who are required to give supporting evidence of the illness throughout the claims process.

This is why it's so crucial for people with CRPS to seek out a specialist solicitor who has a much deeper understanding of their illness, rather than going with one of the larger firms who advertise on TV and radio. Richard says many of the people involved in these companies do not even have legal training.

The likelihood of such firms being aware of the high payout potential is slim. A year ago, Richard won a £1.3 million settlement for a CRPS client who was quoted £25,000 with another firm.

BLB is coincidentally located in Bath, which is where one of the leading CRPS inpatient clinics is situated in the UK.

Richard says many GP's are reluctant to make a referral to this centre of excellence, even if they have the funding for it. Some of Richard's clients often have no other option but to be referred to Bath privately, which luckily they have the finances for, thanks to Richard's persistence in securing interim payments.

Richard talks about CRPS referrals, and the perception of residential pain clinics as "colleges for the damned."

Richard talks about CRPS referrals, and the perception of residential pain clinics as "colleges for the damned."

Pain consultants are also reluctant to refer to Bath. Despite them being specialists and aware of CRPS, they aren't keen to refer their patients because they're under the impression that what they provide on an outpatient basis in their hospitals, is just as good as what is offered by Bath as an inpatient.

For a person to have access to interim payments from the defendants insurance company if they are out of work, Richard must navigate a lengthy back and forth with various parties to ensure these payments reach the claimants bank account.

Like many personal injury litigation claims, the process is far from smooth, and will last many years. Methods used by the insurance company such as covert surveillance tactics are common in personal injury litigation, but can be incredibly distressing for people with CRPS - particularly when they are having a good day with their symptoms, and may manage to walk a little further than normal, or if they are seen to be laughing or having fun.

At any opportunity, the defendants insurance company will try and use such fluctuations in symptoms against the claimant.

Richard advises his clients to make him aware of every event they are attending, perhaps a family wedding or a birthday party, and to email him when they may have walked further than they said they were able to in their testimony, incase they are being filmed by the defendant's insurance company.

Whilst the process is undoubtedly stressful, having a financial safety net should a claim be won, is one less thing to worry about when living with an illness like CRPS.

Why don’t we have a drug that can cure CRPS, and why does diagnosing the condition sometimes take many years?

CRPS is an orphan disease, belonging to a classification of rare illnesses affecting a small percentage of global populations.

Up until the 80's in the US, and the 90's in the UK, orphan diseases carried little to no financial incentives for pharmaceutical companies to invest millions into the drug manufacturing process, which can involve up to a decade of clinical research.

Companies would only get a small portion of their investment back, so development of such medicines were not economically viable.

Orphan drug acts were brought about to financially incentivise Pharma companies to develop medicines for rare diseases - one element of the orphan drug act in the US is a 50% tax credit granted to companies who wanted to develop such drugs. This was slashed to 25% in 2018.

Even with this tax credit cut in half, big Pharma can hugely profit from orphan drugs. Another incentive is seven year market exclusivity for drug companies in the US, and 10 years for EU companies which rather unethically, allow Pharma companies to set whatever price they want for their treatment.

Neridronic acid received orphan status in 2013, and is a type of infusion only licensed to treat CRPS in Italy. It can be accessed for around £15,000.

The drug was trialled at multiple clinical research sites around the world by Grünenthal in 2018, but the study was halted by the sponsor for an undisclosed reason, despite reports from many patients involved in the trials who said it worked.

Unfortunately, neridronic acid is not a ‘cure’, and the treatment does not work for every patient. Since CRPS is so poorly understood, manufacturers aren’t in the position to create a drug en masse that they know will slow or halt the progression of the disease, or effectively treat symptoms.

Even with the incentive from orphan drug acts, until science has more understanding of the pathophysiology of CRPS, it will likely take many more years of research before a targeted treatment for CRPS is available. In the meantime, patients are prescribed a range of painkillers to tackle symptoms.

At the time of writing, there are no more than 18 clinical trials taking place within the EU for CRPS. In these studies, little more is being done than pitting one well known painkiller against the other in a process called drug repurposing, to see which comes out on top in tackling CRPS symptoms.

Only a small percentage of clinical trials on the EU register are testing novel therapies (testing of medicines that do more than address pain symptoms), which means hampered outlooks for patients who are in need of a new, targeted therapeutic specifically designed to treat CRPS and modify the disease progression.

Window of opportunity

There is a window of opportunity for a clinical diagnosis of CRPS to be made, and this is widely agreed by experts to be at 6 months since the onset of symptoms.

The likelihood of CRPS entering remission, and the chances of being able to successfully manage symptoms is far higher when patients are treated within this timeframe. The longer the disease has to manifest, the less likely it is for this person to have the chance of living a pain free life.

Many physicians familiar with CRPS estimate patients on average are diagnosed between 6 months and 1 year after the onset of symptoms, many of them missing these enhanced chances of getting better.

In the survey distributed by Burning Nights, 65% of UK respondents said they received their diagnosis after 6 months. For the US respondents, this number was 53%.

In a comments section where respondents were able to specify the time it took to receive a diagnosis, 17 people were not diagnosed until 3 years after the onset of symptoms, and astonishingly, some respondents were diagnosed around a decade after they first saw a GP.

The problem with being female and in pain

The first interaction a patient has with their GP is crucial to ensure the rest of the diagnosis process goes smoothly. Sadly, this is where it all goes wrong for most.

Being female is a huge disadvantage when it comes to pain. Studies have shown not only do women wait longer to be seen by a doctor when in an emergency department, they are also less likely to be given strong painkillers than men in the ER.

Women are more likely to be dismissed as hysterical, mentally unstable or hypochondriacs, whereas men are far less likely to make so much as a peep when they feel pain.

These gender biases are just as deeply entrenched within medicine as they are in our greater society, and rather unsurprisingly, trickle down into the assessments and diagnostics of chronic pain conditions in female populations.

Being out of touch with your body and health for even a few weeks is distressing, and any person who has experienced a chronic illness or serious injury will tell you this with conviction. Feelings of isolation, loss, sometimes even grief, are only amplified when getting to the root of the problem takes longer than you could have ever imagined.

Such staggering lengths of time before a clear diagnosis is also common in other painful illnesses specific to women. Fibromyalgia and Endometriosis take on average 5 and 7 years to be diagnosed.

Whilst women are four times more likely to be diagnosed with CRPS, it goes without saying that regardless of gender, the chances of living a happy, fulfilled life whilst in the dark about your health are negligible, and of course, men who live with CRPS are in just as much pain as women with the disease.

There are serious and sometimes fatal implications of doctors choosing not to believe a person who reports this type of pain. Throughout much of the diagnostic process for Complex Regional Pain Syndrome, sufferers are often closer to suicide than they are to a referral to see a pain specialist.

The diagnosis process

In February, The Pharmaceutical Journal published a story reporting chronic pain patients to be waiting up to 18 weeks to see a pain specialist in the NHS. Not only does this referral time vary hugely throughout the UK in what is described by CRPS sufferers as a “postcode lottery system”, but this process for many involves the repeated dismissal of symptoms. Sufferers all over the world are at war with these misconceptions most commonly held by the very people who are supposed to take care of them.

If you have the finances to side step this waiting time, you have an upper hand, and may be able to access a private referral, but even then, there is no guarantee you will necessarily be seen by a consultant who has heard of CRPS.

“My physiotherapist was amazing and recognised my condition quickly, but my GP was dismissive. My fracture consultant was initially dismissive until my physiotherapist wrote to him prompting him to take more notice of my worsening symptoms.”

- UK survey respondent

Being on the road to treatment takes sheer determination from physically and emotionally drained patients, who are driven by their pain to be heard, listened to and taken seriously.

Patients struggle to have their voice heard before they are diagnosed.

Patients struggle to have their voice heard before they are diagnosed.

Why is this rarely met with the same determination by a doctor to get to the root of the problem?

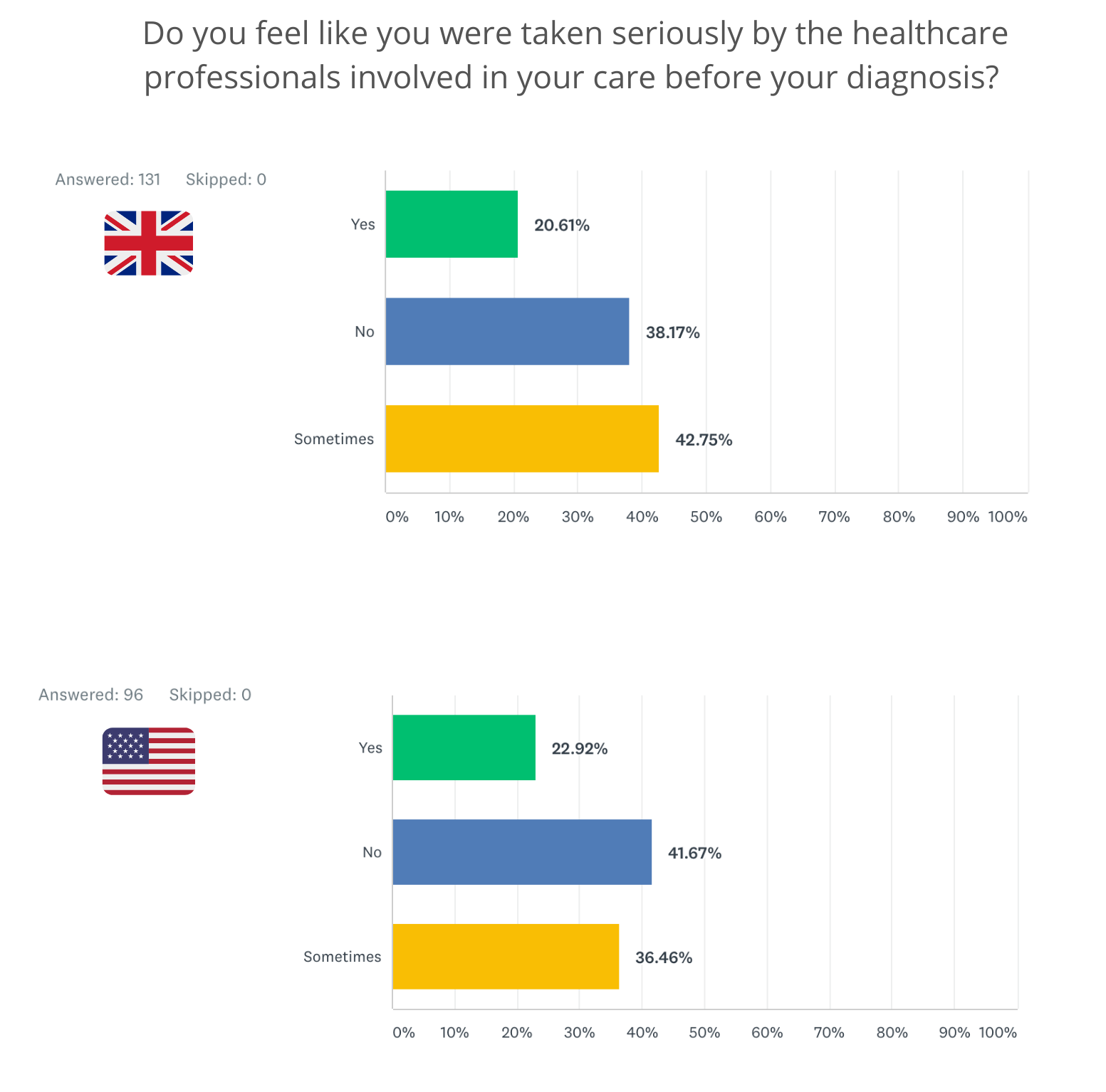

As well as practical limitations to receiving a diagnosis such as where you live, what you can afford to spend on private consultations and the mental resilience you must be in possession of in order to spend this time living in constant, debilitating pain, the actual method of diagnosing CRPS is fraught with obstacles.

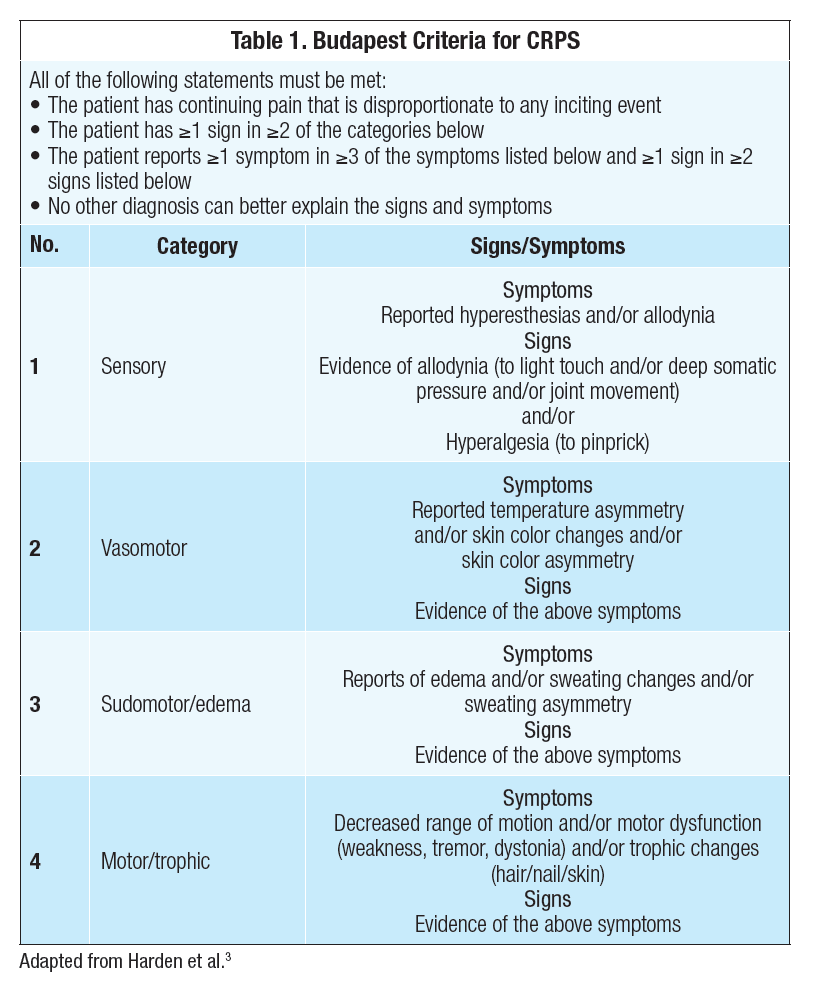

The Budapest Criteria for diagnosing CRPS is a ruling out process, and the clinician is looking to make sure symptoms cannot in any way be attributed to another illness.

This is difficult and time consuming, especially since not all of the signs or symptoms of CRPS may be presenting all at once, as CRPS is an illness which can fluctuate greatly.

The diagnostic criteria exist in this way because as of yet, there is no medical test to detect the presence of CRPS. The illness is known to avert X-rays, MRI’s, Cat-scans and other technologies which would usually be able to hone in on a disease of such distinction.

Whilst these methods do work occasionally, they cannot be used on their own, and not with the same level of certainty that say a PET scan or lumbar puncture would pick up on markers of Alzheimer’s disease.

65% of UK respondents received their diagnosis after 6 months, with just over half of US respondents missing a potential opportunity for their disease to enter remission.

65% of UK respondents received their diagnosis after 6 months, with just over half of US respondents missing a potential opportunity for their disease to enter remission.

Which medications exist to treat CRPS symptoms?

Clinical trials and research studies are the only way advancements can be made in medications and treatment for CRPS.

Since so little is understood about the disease, a cure being on the horizon anytime soon is highly unlikely, but enhancing and fine tuning pain medication so that patients can have a wider and safer variety of treatment options, specifically ones that don’t involve opioids or heavy sedatives, is all possible with clinical research.

Kieran O’Connell is a Patient Engagement Coordinator for a clinical trials company who test new treatments for CRPS.

Kieran has spoken to and screened hundreds of people with the disease, as part of the assessment process which looks at a potential patient's suitability to take part in a clinical trial.

He shares some of the most common problems patients have with referrals, their medication and their side effects.

The list of medication taken by someone with CRPS is often extensive, and will usually include opioids.

Like Kieran says, the chances of a person taking one or two medications to tackle symptoms is almost unheard of, and it’s usually the case that a person is on many different types of painkillers as well as other drugs to protect them from harmful side effects.

Recently, a war on opioid medication has led to unnecessary stigma towards chronic pain patients who need to take this type of drug to live to the best of their ability.

The view of the chronic pain patient as an addict is misplaced, and harmful. Bryan Spece was a chronic pain patient in the US who had his Oxycodone dose reduced by a new doctor, despite doing well on a maintenance dose of 100 milligrams a day.

The return of his pain drove him to suicide by gunshot wound, and his death is likely the result of a new anti-opioid rhetoric, which is seeing many doctors in the US jailed or having their licenses revoked for prescribing opiates to people who need them.

A common medication used to treat patients with CRPS is a tricyclic antidepressant called Amitriptyline. In CRPS, Amitriptyline helps people to get a full nights sleep because of it’s sedative properties, but tends to leave some people almost zombie like.

Maxine discusses her pain medications and their side effects.

Maxine discusses her pain medications and their side effects.

Amitriptyline is effective against several illnesses, and is used primarily to treat a wide range of mental disorders such as major depressive disorders, anxiety disorders as well as neuropathic pain.

Side effects listed as common in the drug manufacturers information guide include mouth pain, a black tongue, decreased sex drive and difficulty reaching orgasm.

Other side effects are incredibly severe and live threatening - Maxine lives every day knowing one of her medications, Duloxetine, could be damaging her heart.

One of my survey questions asked respondents to recall some of the most frustrating things they were told by healthcare professionals in the time leading up to their diagnosis.

Modern medicine can do better than this.

Whilst we cannot expect all doctors to know the intricacies of every single disease, what patients should be able to expect, is that they are believed when they report being in pain.

Just because a physician has not heard about an illness, does not mean the illness doesn’t exist, and patients must be given the benefit of the doubt rather than having their sanity questioned, resulting in more stress, and more pain.

Referrals need to be made quicker, without hesitancy. There needs to be more education about CRPS within every level of healthcare, so that a referral is not the result of a stroke of luck.

Although many have been failed, it is not too late for the thousands who are unaware a future accident or scheduled surgery is going to result in the onset of this illness. We can change the outcomes for these future patients by mandatory training sessions on diagnosing CRPS, to bring the diagnosis of the condition safely within the 6 month window of opportunity, or ideally even earlier.

Thank you to everybody who participated in this project.