Boxing & the Brain

A discussion surrounding the red flag being raised in the world's most popular combat sport?

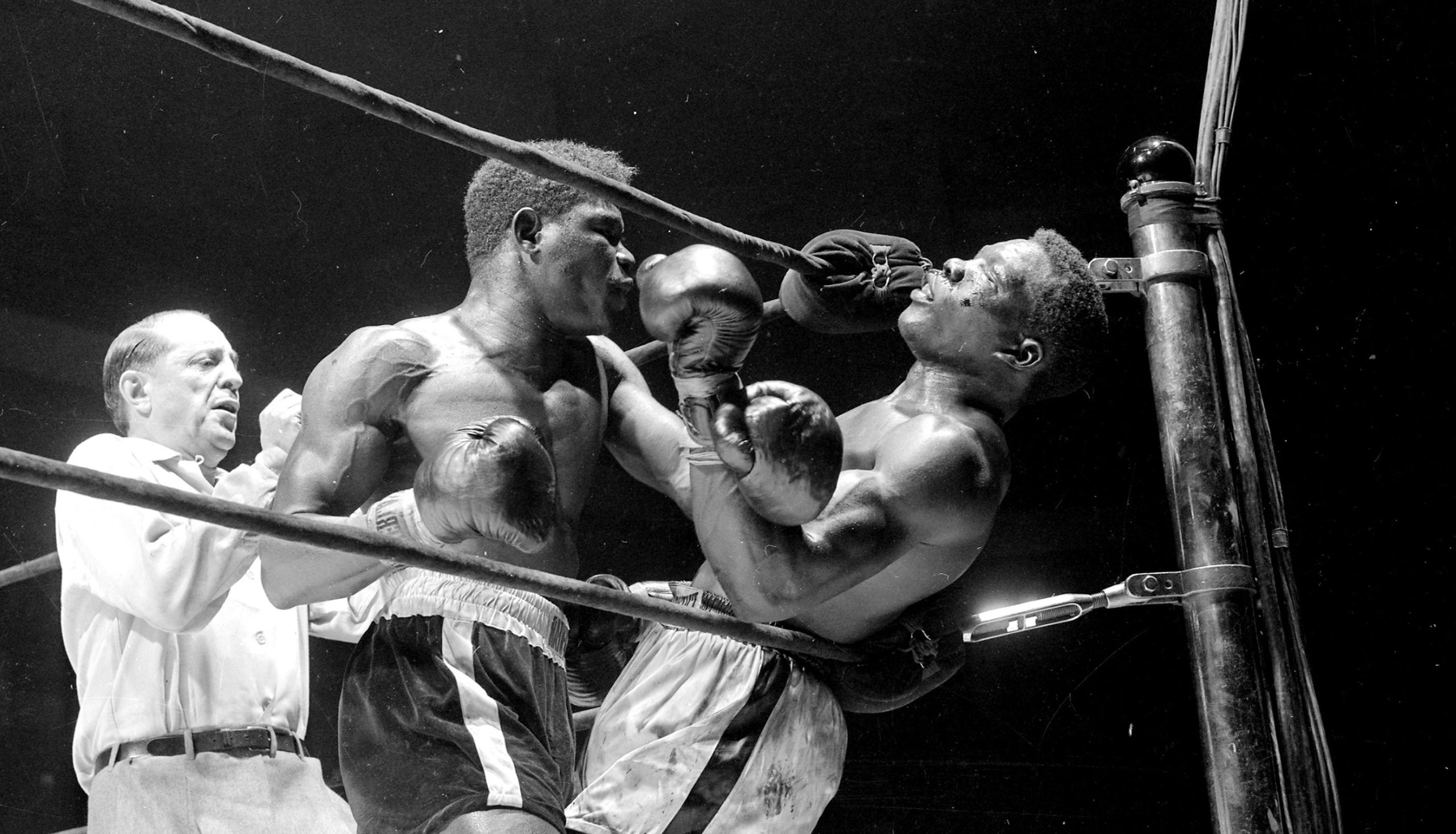

It's best to start by explaining why boxing has such a special hold on the world of sport. It transcends the competitive nature of an athlete by bringing into play the primal nature of man. In terms more appealing, watching two men try to cave each other's heads in for repetitive rounds is quite exciting. There are bust lips, broken noses and black eyes, which are all part of the journey towards the most emphatic ending in sport - the knockout. That culmination has been the end goal in boxing for over a century and is what makes it one of the most exhilarating, taxing yet money-generating sports on the planet. But as the sport grew from the underground prohibition bars of 1920's America to the bright lights of the Las Vegas strip, with it remained a timeless problem.

The beginning of 2020 has relevantly helped spark a conversation about the sport's two biggest obstacles. The story surrounding the 'mega-fight' between Tyson Fury & Deontay Wilder overlapped the conquering of a severe battle with depression, whilst opening once again the conversation surrounding fighter safety. However, 2020 hardly opened a can of worms untouched before.

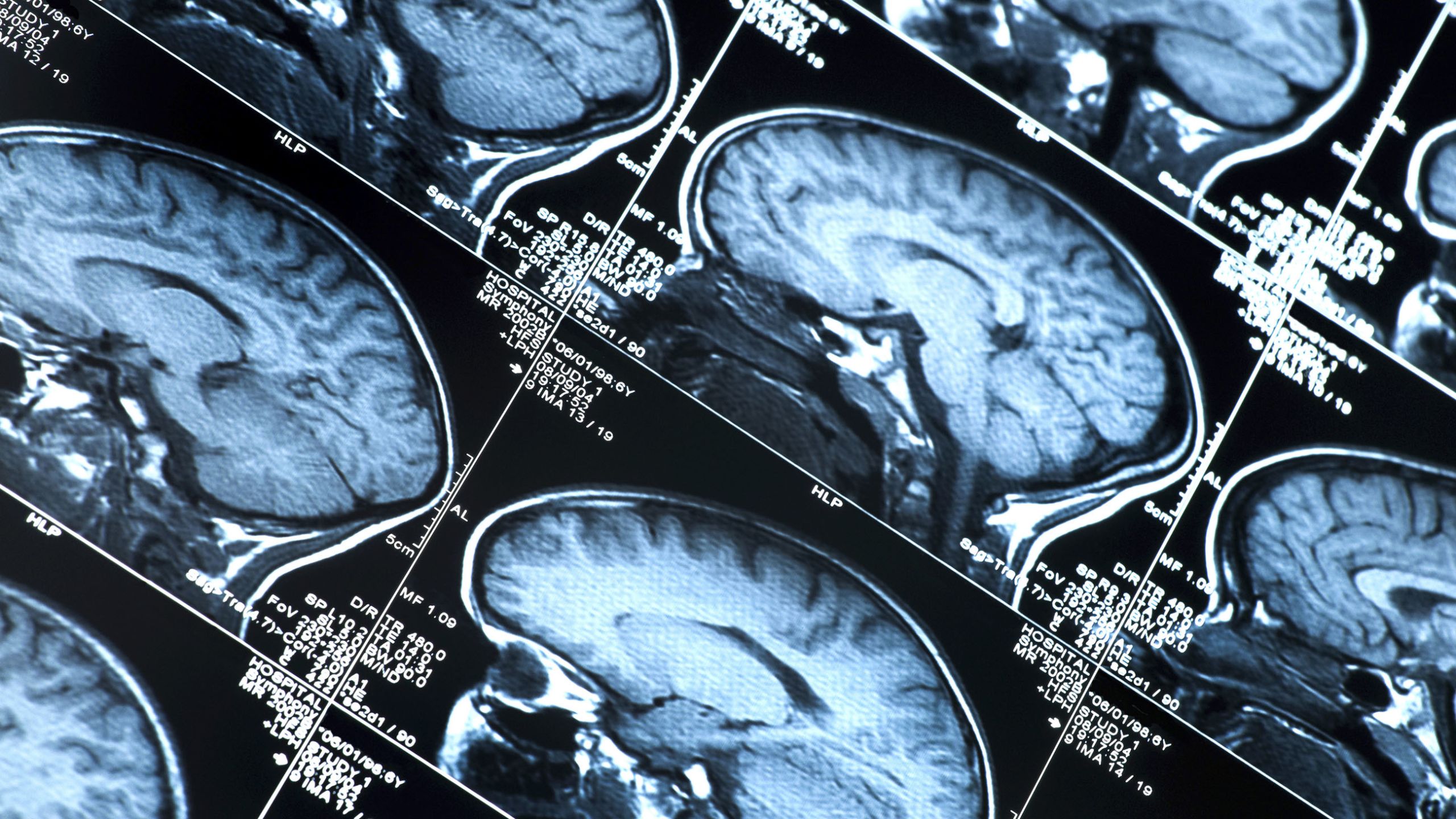

In 2019, boxing lost four fighters on the professional circuit. The first was Maxim Dadashev (pictured left), a Russian light-welterweight who was billed as one of the country’s biggest prospects. The second was Hugo Santillan, who passed away a mere 23 years of age in his native Argentina. The third was Patrick Day, who was fighting on one of the year’s most high-profile shows in Chicago. The fourth, Boris Stanchov, a native Bulgarian fighting in Albania. All four of these warriors were hurried to hospital, where all four received the highest level of care - care that included them going under surgical procedures. All four died of causes relating to bleeding on the brain.

‘I think people understand that fighters get hurt in this sport’, said promoter Lee Eaton. ‘I can’t fight for them, although sometimes I wish I could, because these guys don’t know how to quit. They will fight to the death.’ Lee, 34, has promoted over 100 shows for MTK Global, one of boxing’s foremost management and promotional companies. ‘I haven’t had a tragedy yet. But it’s an odds game, if I do this into my 50’s then I’m sure there will be dark days’

To many, the conversation around the prevention of such tragedy’s may seem something modern, something that aligns with our everyday culture becoming more safety orientated. However, you can go back to 1928 and the study of a certain doctor which would change the path of boxing neurology forever.

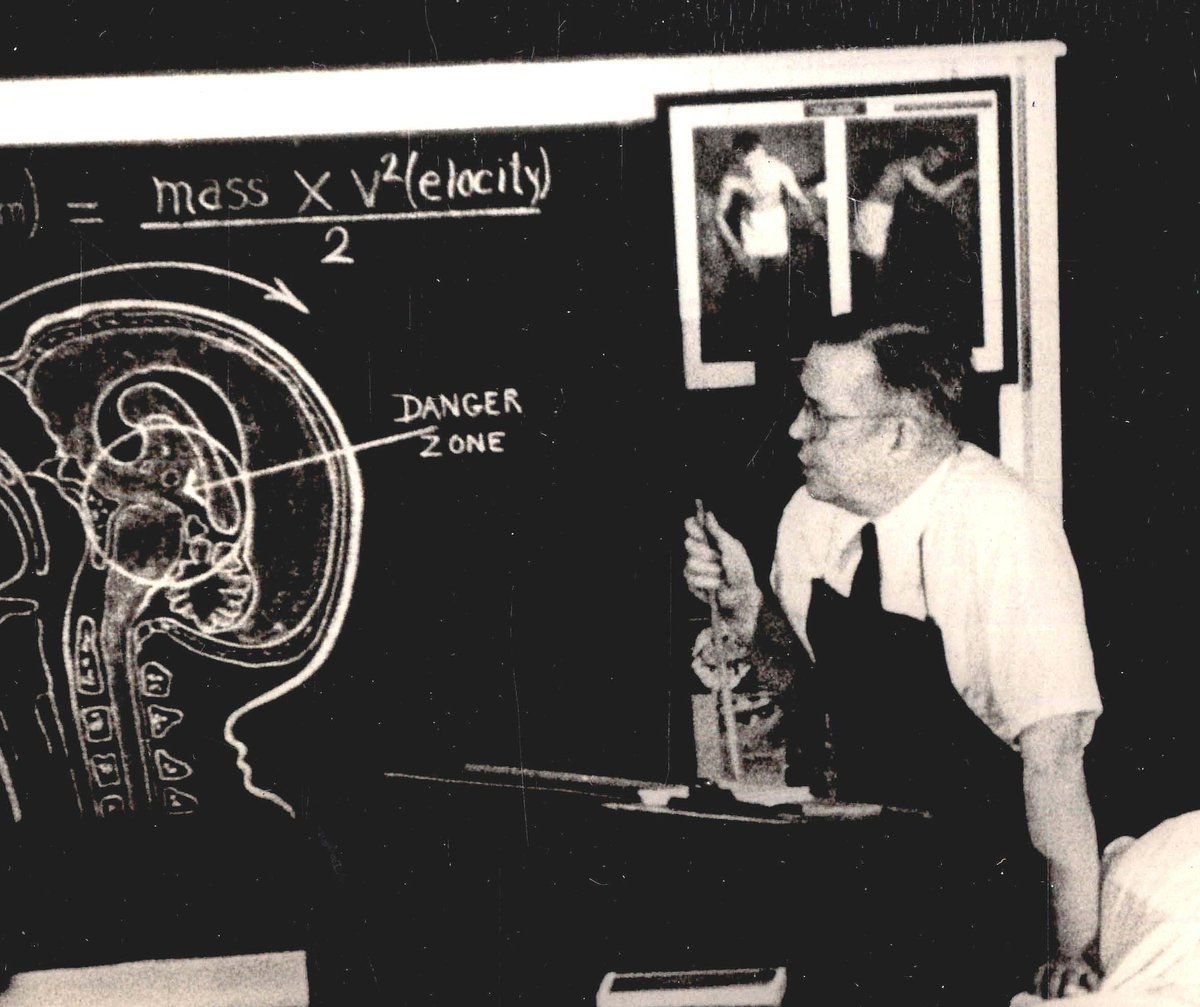

Dr. Harrison Martland (pictured right) was an American pathologist who began the use of the term ‘punch-drunk’. In one of his many JAMA (Journal of the American Medical Association) publications, he noted the slurred speech, sluggish movement & shakes caused by trauma on the brain - he likened the symptoms to that of someone under the influence of alcohol.

Dr. Martland can also take acclaim as being one of the first men to attribute Parkinson's disease to repetitive brain trauma.

In boxing, Parkinson's disease will forever be associated with the late, great, Muhammad Ali. In the lead-up to his historic fight with Larry Holmes, Ali was assessed by some of Nevada State’s best neurologists, who were aware of deterioration in his brain. Even so, Ali was cleared to fight, and he was beaten up badly. 4 years later, Ali contracted Parkinson’s.

Even to this day, many still suggest that Ali's Parkinson's was a mere coincidence, and not at all attributed to a boxing career spanning 21 years. By the time Ali passed in 2016, he was a meagre shadow of the charismatic figure that bought boxing to the mainstream.

Of course times are different now, and Ali would not have been allowed near the ring had said circumstances occurred 30 years later. But does that change whether he would have?

The current boxing climate is at it's best ever. Fighters now can walk away from the sport with career earnings that would surpass the GDP of a small African country. The 'Mayweather effect' they call it. So with the capability to support your family for generations beyond your own, do you really think these fighters are thinking about brain trauma on fight week? Of course they're not. In fact, I'm not really sure anyone is giving it a second thought.

After the aforementioned Patrick Day was carried out of the ring on a stretcher last year, a carefully assembled commentary team of ex-fighters and 'experts' gave their sentiment to what would have been a fairly large audience on American network TV. What struck me, was the lack of knowledge of a situation that many of these guys had likely seen before.

Sometimes, I even ponder as to whether the doctors are as in the know as they should be. I've been in many a dressing room where a fighter has returned after taking a significant amount of punishment, to be greeted by a doctor with nothing but a torch light and rubber gloves.

I don't think you can put a finger on anyone specifically. Not that I really want to. Collectively boxing needs to come together with an issue like this. Even the fans play a role more significant than they realise.

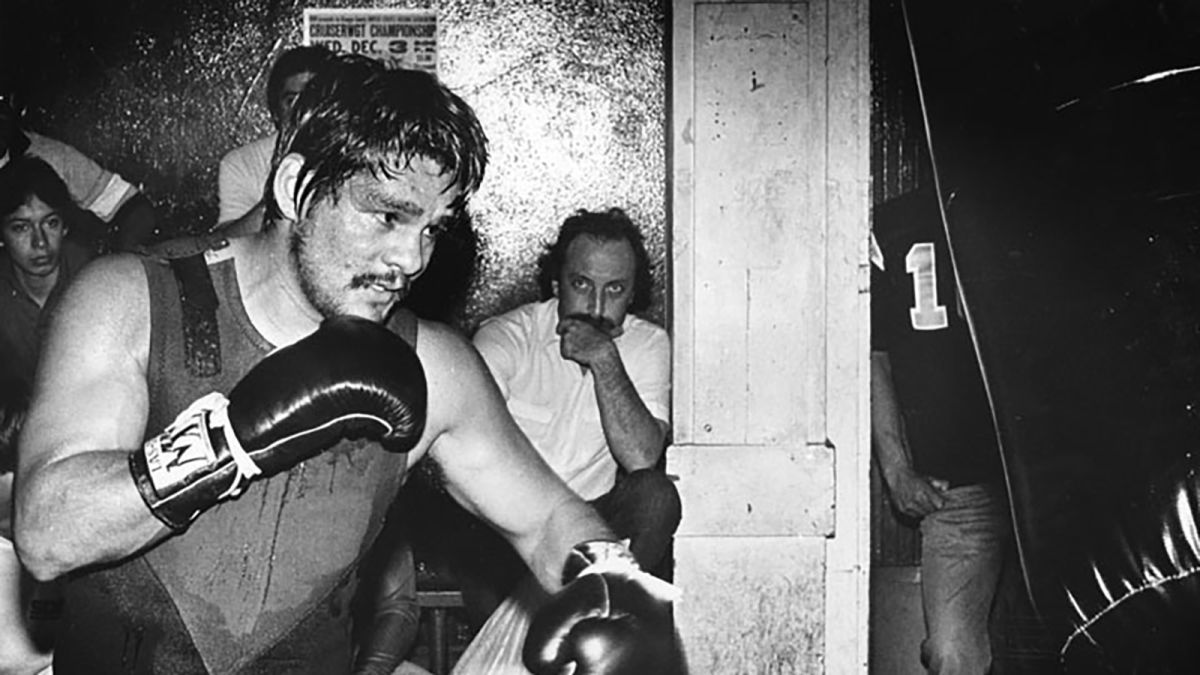

The term ‘No Mas’, was made famous in 1980 when Roberto Duran (pictured left) echoed the words to his corner, meaning he wanted ‘no more’ of the beating he was taking from Sugar Ray Leonard. Duran was lambasted by the fans and hung out for slaughter by the media. Once a flag-bearer for his beloved Panama, he became a enemy of his people.

Imagine adding to that the social media tools we have now. It suddenly becomes quite clear to see why things aren’t getting any easier for fighters who face the dilemma that Roberto did.

If a fighter is a taking a pasting in the ring, then what’s wrong with quitting for their own safety? As the legendary Heavyweight Max Baer said, ‘fans are entitled to see a fight not a slaughter’.

The promoters are important too. If truth be told, they're probably the ones who get scrutinised the most.

Whether it be direct matchmaking or general safety precautions, these guys have a duty of care over their fighters and events.

Last year, I was part of a media team that covered boxing across the globe. We sat down regularly with Eddie Hearn, promoter of Matchroom Boxing, who candidly spoke after one of his London shows about why ringside oxygen is so important (below).

As well as ringside oxygen, there are several other changes that have been petitioned by many involved in the sport. Luckily, when working away in the States, I came across Jack Hirsch, the former President of the Boxing Writers' Association of America. Jack has been in and around the sport for nearly 40 years, but he's not your traditional 'old man in a young man's game'. Quite the opposite.

Jack has written several articles and done a lot of research into how the safety aspect of boxing can be improved.

'It wasn't hard to find my drive for this. I have friends, one specifically, who many would call a legend of the sport - I have rung him for a phone interview before, only to be rung back 20 minutes later with no memory of our conversation.

It's a sad state of affairs when we consider the lucky ones to be people who walked away without serious brain damage.

Boxing will never be safe, but what hurts the most is seeing the work of those who want to improve the safety of the sport, being gravely ignored'

Jack works mostly in America, where rules and regulations are enforced by a different body to over here in the UK.

Here, we have the British Boxing Board of Control. They have a strict set of rules which are needed to be met by fighters who want to obtain a professional boxing license. Many of these rules are in relation to the license holder's medical history, in an attempt to keep them as safe as possible.

29-year-old Michael Elliott (right) was at the start of his boxing career. With his 3rd professional bout on the horizon, he was stripped of his license by the board due to an irregular brain scan. 3 months down the line, he was forced to give up the sport he loves.

Now, he struggles with his speech and brain activity. But he still considers himself grateful, as things could have been a lot worse for the ex-Marine.

These are just a few of many altercations that could be made to keep our sport from falling into more tragedy.

It will undoubtedly take the hard work of a large number of people, and could take years to implement with the financial strain that is to follow. Nevertheless, boxing simply cannot continue on this path to self-destruction.

I have tried to incorporate a limited number of figures and statistics in this piece, because the facts would suggest that these fatal incidents we speak of are few and far between. Ultimately, this would be correct. Yet every time it happens it feels worse than before.

'Let's say the fatality odds are 1 in 5,000. If you put 5,000 fans in a stadium, and told them all that 1 would be beaten to death for the entertainment of the others, well, when you do pick that name from the hat, everyone will be wincing'

So for Maxim, Hugo, Patrick, Boris, the thousands before them and the thousands that will come after - we salute you.

Because it's easy from this side of the rope.

So as we push forward into uncertain times, boxing has bigger obstacles than ever to overcome at the moment. As it stands, there will likely be no boxing until July. Even that is on a behind-closed-doors basis. For the companies with a smaller budget, or the professionals who combine their boxing career with a 9-5 job - it could take even longer.

However when the sport does return, perhaps the emphasis that will be placed on protecting those involved from COVID-19, can also be placed on savings the lives of those battling it out in the ring.

Oscar Bevis