The danger of being poor and gay in Morocco

the inequality effect on the LGBTQ+ experience of Moroccans

This year has been more than important for the LGBTQ+ community in Morocco.

It all started in April 2020, a month after the beginning of the lockdown in Morocco where a real homosexual hunt, a ruthless harassment campaign on the internet has been raging. One influencer, who is herself Moroccan and a member of the LGBTQ+ community, asked her thousands of followers to use gay dating apps to track their users and make their identities public on social networks.

If you are reading this article from a country where homosexuality is not a crime against the law, you must have already thought that this is a horrible invasion of privacy, but here it is much more serious.

Article 489 of the Moroccan Penal Code criminalises "licentious or unnatural acts with an individual of the same sex ". It can be punished with anything between six months and three years imprisonment and a fine of 120 to 1,200 dirhams it should be noted here that the average salary per month is of 2300 dirhams). According to a report by the Prosecutor General’s Office released in 2019, the state prosecuted 122 individuals in 2019 for same-sex sexual activity. It should also be noted that antidiscrimination laws do not apply to LGBTQ+ persons, and the penal code does not criminalize hate crimes.

This attack quickly caused a lot of drama and the LGBTQ+ community became the target of blackmail, suicides, violence, sometimes even by their own families. The press reported numerous cases of harassment, and assaults resulting from these outings, and some victims reported receiving death threats. As of April 20th 2020, LGBTQ+ groups indicated at least 50 individuals were targeted as a result of Instagram live video; of whom an estimated 21 were physically abused or rendered homeless and several others committed suicide.

Besides the law, it is not uncommon to hear of public lynching of homosexuals or other acts of hatred towards them not committed by the authorities. In 2015, for example in the city of Fez, a man presented as a homosexual was lynched in the street by a crowd. He ended up collapsing to the ground before the police arrive; A barbaric scene. We also need to keep in mind that no studies have been conducted on the nature and spread of violence against LGBTQ+ persons in Morocco. Subsequently, there is an absence of concrete statistics. According to the Newspaper Morocco World News, At least 70% of the community reported being subject to some form of violence due to their sexual orientation.

But the inequalities do not end there, among the members of this same community some risk more than others. Young men and women from poor families are affected differently, yet they are often the ones leading the fight.

Thus, after this year's wave of homophobia, began a real call for revolution. But a revolution that will be led by whom? This article, will tell you about the stories of strong personalities, people who dedicate their daily lives to the LGBTQ+ cause in a country where even kissing a person of the same sex publicly is illegal.

“The LGBTQ+ fight is a fight led by the poor when they are the ones that risk the most”. -Abdellah Taia

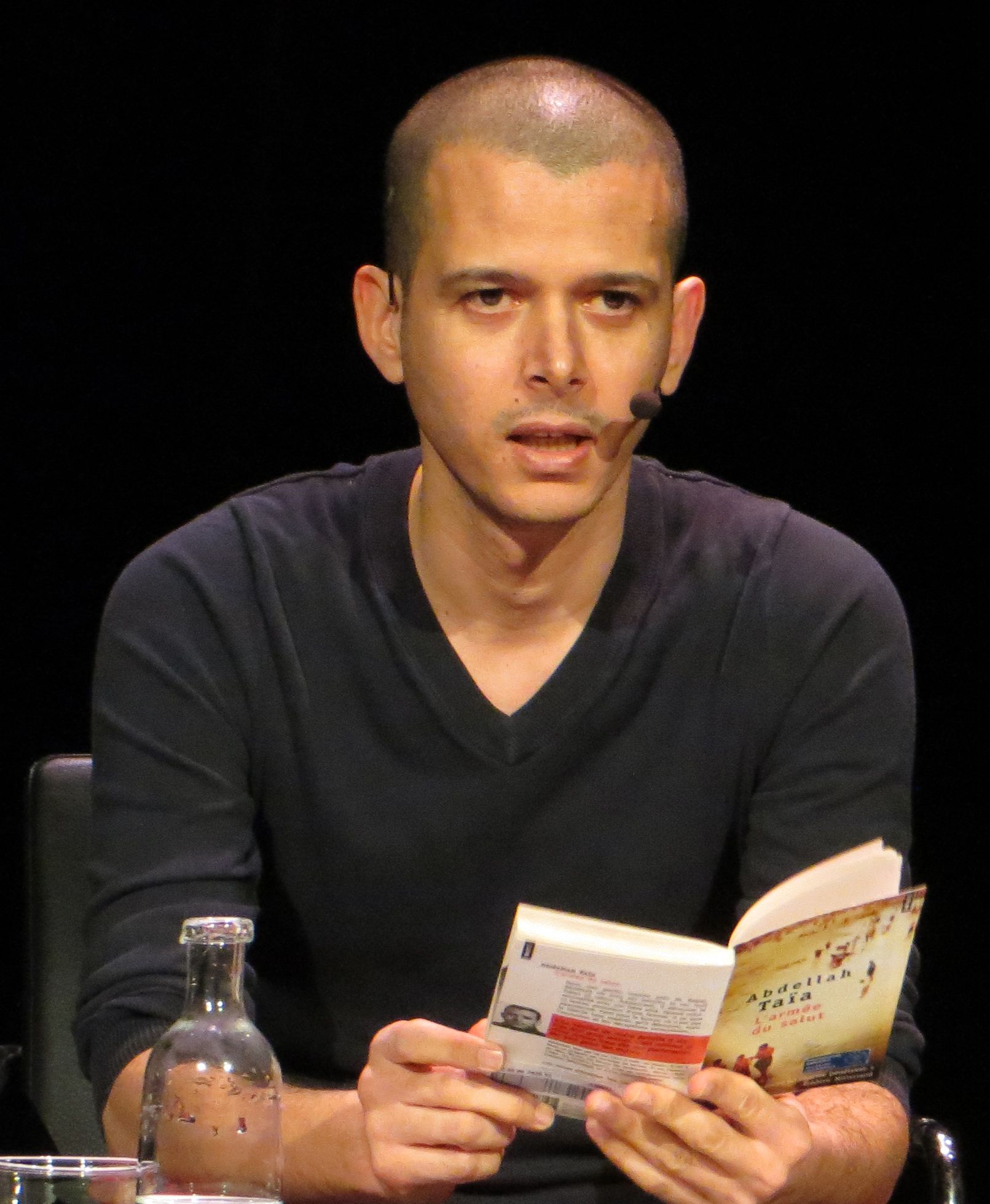

You can’t be talking about gay rights or the LGBTQ+ community in Morocco without talking about Abdellah Taia. Abdellah himself is a symbol: In 2006, he became the first openly gay Arab writer after having publicly declared his homosexuality in the Moroccan press without a pseudonym under the title: "Homosexual, against all odds". A strong symbol, he remains one of the only openly homosexual Moroccan writers and filmmakers.

What was supposed to be a project about LGBTQ+ culture, people flipped entirely to the deeper issue when Taia spoke during our interview

“The LGBTQ+ fight is a fight led by the poor when they are the ones that risk the most”.

And he was right. Abdellah himself comes from a working-class background. He explained that the LGBTQ+ cause has been abandoned on one hand by the political world but also by all the most wealthy classes, that is to say, the people with the power, who own large companies or political figures etc..

"Today, many people speak out and express themselves, but the government acts as if these people do not exist. It is a minority that is real and that imposes itself. But the political world pretends that this minority does not exist.”

He also added that most of the people who are trying to make things happen here come from the working classes.

“There are no rich people, or children of rich people, trying to do anything. Almost all of them are poor kids. There is a total resignation of the upper classes and their children. That's what I call social racism. These people put blinders between themselves and Morocco. The children of the mission (foreign school) live in another reality. As they live among themselves, they don't actively risk anything so they don't revolt.

Even if the police discover that they are queer, they will even further decode that they are bourgeois before leaving them alone. Even despite themselves, these children see Morocco from above. They represent only 2% of Morocco, but they dominate it without realizing it. Why? Because their parents hold the power, the big industries, the high positions. Beyond that, some people take risks, sometimes risking their own lives.”

To get more information about social injustice in the LGBTQ+ community interviewing Sofiance H was obvious.

Sofiane H was born in 1991 in El Jadida, Morocco. He is a Doctor in health science and since 2011 an independent activist for LGBTQ+ rights. For the past few years, he worked on the ELLIE project, a tool for popularizing issues of gender and sexuality through art and culture. He’s also the creator of the platform “Machi Roujoula”, a sharing space where people can debate about toxic masculinity in Morocco.

Sofiane H is a part of a new generation of activists who want to be heard.

“My activism is based on writing and art, through visibility. The reason being that not many people are interested in this cause. Unfortunately, this cause has been abandoned by intellectuals and organisations. People do not take it seriously and apart from the fact that these people are discriminated against and in danger, their freedoms are also in danger. By that, I mean their access to education, or health care for example.”

When asked about social inequalities, here is his response:

“The poorer and queerer you are, the more you suffer. You have no privileges, no family names and you are more likely to be arrested by the police.""

"Indeed, in a corrupt system like Morocco, the poor are already the most vulnerable. For example, it is considered more legitimate to have sexual freedom in a 5-star hotel among rich people than in a working class area like the medina. Then comes the power of the 'Moroccan big names' who almost serve as a 'free pass' for the police.”

But Sofiane didn’t stop there, for him the inequalities are present even within this community where everyone isn’t treated equally besides the social class factor.

“We have already talked about social classes, but there are other factors that come into play, such as skin colour or conformity to one's biological gender. All these parameters have created a certain hierarchy of injustices. And so finally when you are rich, when you have a gender expression that conforms to your biological sex, when you have a lot of privilege in society, you work, you live in a big city. I.e. if you are more socially conformed, homosexuality finally becomes less problematic. All these are factors that make homosexuality and the LGBTQ+ issue strictly linked to social injustices.”

Abdellah Taia

Abdellah Taia

Illustration for the podcast "Machi Roujola" By Zaineb Fasiki

Illustration for the podcast "Machi Roujola" By Zaineb Fasiki

An inequal country

Life in Morocco seems perfect and if you’re lucky enough to be a part of the wealthy people it is an absolute dream. It’s the perfect cocktail: add sun, palms to the comfort of maids, drivers, villas and private school and you have a peek through the keyhole of how privileged people live their life. It seems perfect and when you’re in that bubble, it appears perfect, but the reality of it is way less glamorous.

If this small circle is able to live this life, it’s because half of the population is living the opposite way.

In reality, Morocco has the Highest Inequality Index in North Africa, meaning that it is the region’s largest gap between the top and bottom of the socio-economic ladder according to the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development.

Most Moroccan politicians, lawmakers and wealthy individuals educate their children in private schools and are treated in private hospitals, widening the social gap. If you want to be immediately aware of those inequalities you only need to go for a walk around such schools. In general, rich people in Morocco put their children into foreign private schools (typically French schools or American schools). In those schools, people have no perception of the value of money when half of the population struggles to attain basic living standards. It’s not their fault, when you live in a bubble it’s hard to see the outside of it. Drivers, house staff, designer clothes, alcohol, drugs, villas, clubs and yet, you only need to walk around the city to see that most of the population is struggling financially. People here are either extremely poor or extremely rich, a middle class barely exists.

During an interview with Sophie Villaume, a sociology professor at the French high school of Marrakech, she said “to state the facts, The Haut-Commissariat au plan, which is the body responsible for the production, analysis and publication of official statistics in Morocco cannot establish whether there is a middle class". According to her, the reason behind such a large gap is a lack of proper wealth redistribution. She went on to say: “Because of the corruption, not everyone declares their income. What’s very ironic in Morocco is that in contrast to Europe, the least-qualified find work more easily. The minimum wage is at 2800 DHS (approximately 230 pounds per month)”.

How can you redistribute wealth when taxes are poorly paid? This paradox occurs where the individuals running the big industries don’t want to invest in their employees. That’s what Villaume likes to call 'the grocer’s vision': “They don’t see the benefits of investing on their employees because they want the money now. As a result, the salaries offered are lower than the investment in their studies. Thus, the young graduates immigrate to other countries to be paid what they deserve or at least more than what they invested in their studies. Additionally, the state does not want to make the average wage higher because of the attractiveness of cheap Moroccan labour to foreign companies.”

Today in Morocco, more than 1.6 million people remain poor and 4.2 million people remain vulnerable - that is to say, at risk of falling into poverty at any time.

What’s very surprising is that Morocco is a country that is always evolving. The state does everything so that the country could be on the international track and not underdeveloped so it begs the question; Why is it so hard for these inequalities to diminish even though the country is evolving?

To that, Villaume answered that, besides all the reasons she said earlier, it’s mostly because public education is failing. One of the ways (if not the most important one) for the working class to improve their financial situation is through education. The public system is failing to provide a good education. Even if improvements are being made, it’s still not enough. Until recently, school education was compulsory until 13 years old only. For the working class, education is useless; they underestimate the benefits of diplomas. It’s also the reason why the upper class and the Moroccan bourgeoisie send their children to private (though frequently foreign) schools in Morocco.

Besides money, other privileges come with being wealthy in Morocco. One of them is protection.

Take the example of young people in Morocco. The golden youth fears nothing and no one, it lives in it's own microcosm, falling to mix. When things go wrong, dad's arm is large enough to erase any annoying traces. After all, appearances still have to be saved.

THE COLONIAL DREAM

Being gay as a foreigner compared to a Moroccan in Morocco

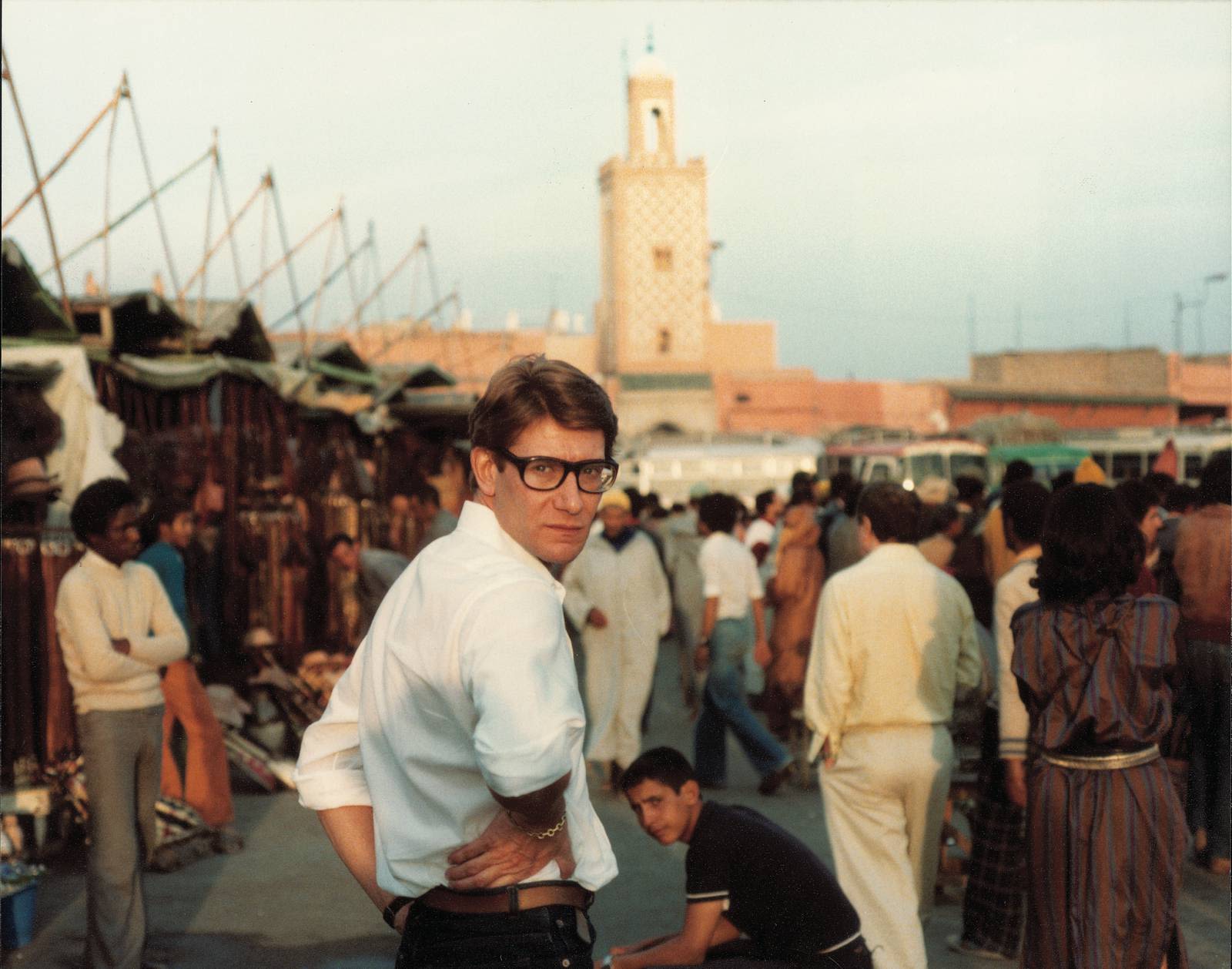

Morocco is known to attract many people from the LGBTQ+ community, especially the French community for many years now. The famous fashion designer Yves Saint Laurent used to have a real passion for Morocco. He and his companion, Pierre Berger, made the city of Marrakech their home. When he died, his 'adopted country' paid tribute to him by naming the street of his house in Marrakech after him. Today, it is in this same street that we find a museum dedicated to his creations and his passion for Morocco. Isn't it strange for him to be celebrated in country where his sexuality is outlawed? Besides the fact that Yves Saint Laurent had global influence, being foreigners seems to have more freedom when it comes to the law about homosexuality.

I spoke to Bernard, a French gay expatriate who has lived in Marrakech for 8 years; Before starting the interview, Bernard wanted to make two things clear:

“I was living in Marrakech in the popular district of the medina (the old city). My life and feelings would probably have been different if I had lived in an upscale district of the capital city, Rabat.” Indeed, residence in a city, in particularly Rabat or Casablanca, offers some level of anonymity and a heterogeneous landscape that contributes to protecting LGBTQ+ persons, while on the other hand, in medium-sized or small towns and rural areas, especially poorer boroughs where the risk of violence is higher.

He also added that he moved to Morocco 14 years ago and left 6 years ago. During those 8 years, he said that for him, the mentality has changed a lot and not in the sense of tolerance or openness...

When asked about his living conditions and what was it like to be gay in Morocco, Bernard said that you’re never officially gay in Morocco:

“It is not something you can say. Everyone knows, but we never talk about it". For a Moroccan gay, he explained that he is confronted with the problem of the "Chouma”.

“It's a concept impossible to clearly understand for a non-Arab/non-Muslim. It’s kind of a shame that applies to the entire family and not to the individual itself, and this is only one aspect of this particularism where religion and tradition mingle, without yet anyone that can explain which take precedence in both.”

Without any doubt, Bernard knew that he was being treated differently but after finishing this project, I don’t think he could even realize how much he was treated differently.

When asked if he had ever faced any forms of threats or discrimination he answered "no". He never faced any open threat, neither physical nor moral; “Simply a sort of ostentatious contempt on the part of some in my neighbourhood”.

However, during his time in Morocco, he struggled to find places to freely express himself where homosexuality remains taboo.

“Everyone is suspicious of everyone else, and they are right to be. No one would dare to talk about it if there are more than 2 or 3 people present. There are some underground associations but they are harassed by the police and the justice system and the leaders of these structures do not last long.”

He nevertheless, surprisingly, said that it wasn’t hard to find a sexual partner, that it was even “very easy”. “Every young person is stopped from having a 'free' sexuality with girls, but having natural sexual urges to satisfy are open to a stealthy and hidden act, without much difficulty.”

However, he did make two points. First, he said that being “passive” in terms of practices remains the exception. In the Moroccan imagination, and Arab in general, one is not homosexual when one is “active”. Secondly, to give himself a clear conscience, the Moroccan who is going to have sex is always gonna ask for a bit of money 'to help the family'.

“One of my partners was explaining to me once that God forgives the sin in this case. He will, although, frequently invite me to have lunch to pay me back what I gave him the day before.”

However, actual Moroccan people have other opinions when asked about foreigners from the LGBTQ+ community coming to Morocco.

During an interview with the author Abdellah Taia he explained: “At the time of the protectorate in Morocco, the Europeans did what they wanted with the bodies of the Arabs. This memory is still there, in people's heads and it's horrible". Abdellah had a different answer to why foreigners seemed to enjoy Morocco that much. For him, the reasons why so many gay people settle in Morocco, despite the laws, are called orientalist and colonialist. “Europeans continue to see Moroccans as something that somehow 'belongs' to them". After indicating that it was not a generality, he divulged in what he calls “the colonial dream.”

The French Protectorate in Morocco was established in the form of a colonial regime, imposed by France, while preserving the Moroccan royal regime under French rule. The protectorate was officially established 30th March 1912 and lasted until 1956. Morocco's independence did not mean an end to French presence; France continues to influence Morocco in numerous ways. The laws, for example, have been modelled on French laws, including Article 489, which refers to laws criminalising homosexual acts. Nevertheless, this law, like many others, concerned only the natives, applied according to the protectorate for the purposes of "protecting the 'Muslim particularity' of Moroccans". Subsequently, after independence, the penal code was drafted, keeping its laws, considering them as a step towards modernity with France as a model.

“In the memory of many Europeans, we are considered inferior to them and they don't notice it. What authorizes a European to come to Morocco and f*** all the Moroccans he wants, without ever being incriminated, while the Moroccans will pay the price?”.

In regards to different treatment, Bernard's comments support this. Abdellah continued: “When in the future the foreigner will talk about Morocco, he will talk about its hypocrisy, while he benefits from this hypocrisy. It is this hypocrisy, the fact that Moroccans deny being gay, accompanied by this feeling of power that attracted them in the first place”.

Nevertheless, for him, The Westerner in Morocco feels guilty and swims in an ocean of contradiction.

“Europeans say that Moroccans don't want to admit that they are gay, but gay according to whom and according to what? They don't understand that Moroccans from the working classes manage as they can in their reality. If they admit that they are gay, they lose everything and put themselves in danger.”

Yves Saint Laurent street

Yves Saint Laurent street

Vestiges of colonial architecture in Marrakech

Vestiges of colonial architecture in Marrakech

Vestiges of colonial architecture in Marrakech

Vestiges of colonial architecture in Marrakech

"When I kiss a partner that’s a win, when I’m sharing my opinions that’s a win, when I care for other queer people that’s a win"

Interview of a young influencer about his life in Morocco

This is the story of a young moroccan activist telling me about his experience of living in Morocco.

"When you think about it, the social class metric is the factor that is always overlooked in analysis. We arrive to the point that we do think about gender and race because these subjects are so apparent now in Morocco, but the social class factor is nowadays very overlooked and not correctly taken into consideration. It’s taken for granted that rich people are rich and every privilege that they own is because they worked for it but in Morocco, it’s not always the case. It does not mean that you’re having it easy when you have money, it just means that you have privilege that makes it easier, especially in this situation".

Fagouta (2020)

Fagouta (2020)

"Privilege is comfort, so when you ask people to give up on some of their privilege, you’re asking them to let go a part of their comfort. What they don’t understand is that this comfort isn’t natural, it’s not theirs, they are stealing this comfort from other people and the reason why they are comfortable is because other people are not. It requires them doing work, active work to put your privilege at the service of the unprivileged".

"One of the things that I thought about a lot, especially when I went to study in Paris, is that the idea that I have of 'gayness', queer men in general, the images that I had of a gay man while living in Morocco were only negative images: Images of men being beaten in the street for looking feminine; Trans people; Sex workers being beaten by the police. In those images, videos [were] always [of] someone that had no privilege. It is the only thing that you see around queerness in Morocco and then there is Abdellah Taia himself that comes from a working class family and was able to give that image, explaining the inside only by existing".

"The reason is not that they are the only people being feminine, for example, but they are the only people that are truly vulnerable. When you are a cross-dresser and you’re rich, you can always cross-dress in your villa and live your life but when you’re a cross-dresser from a working class family, the police will arrest you at some point because you have nowhere to hide. So those are the people that are visible".

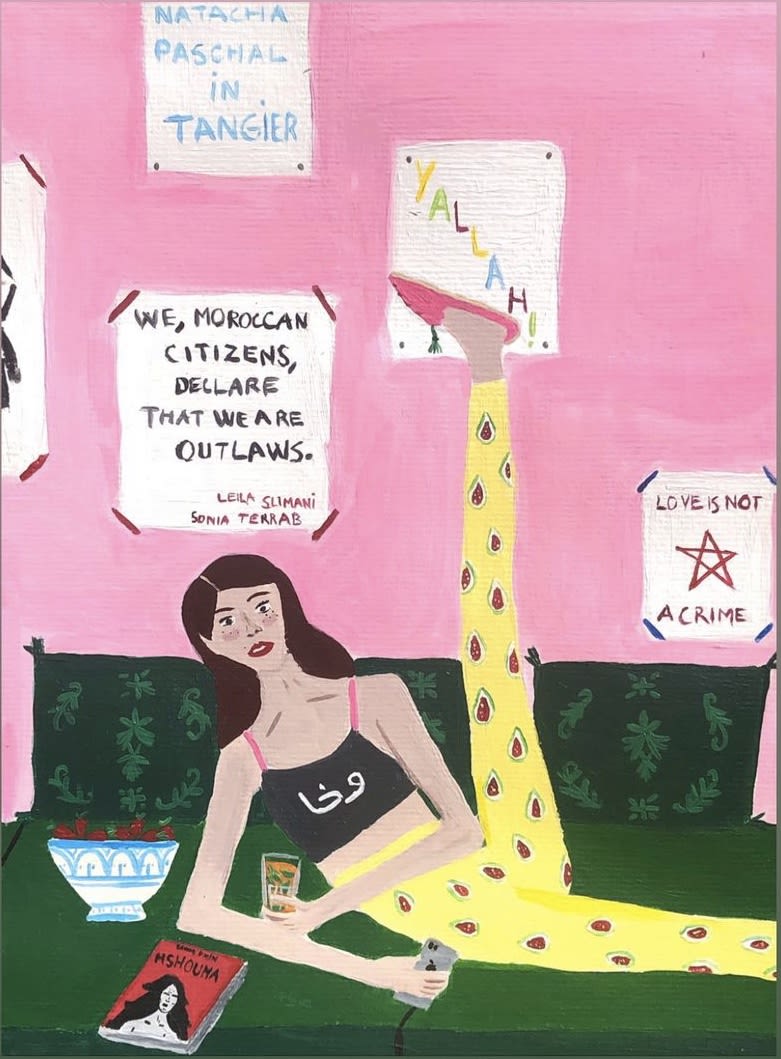

Myriam au citron "Love is not a crime" (2020)

Myriam au citron "Love is not a crime" (2020)

"I was always on instagram under many usernames. At the beginning, I was on Instagram, like everyone else, to post photos of my life etcetera and little-by-little, it has evolved. I wanted to still share everything that I’ve learned in my experiences. My platform isn’t very big and at that time it was even smaller but I felt like I connected with people in more intimate ways. Random strangers will come to me with their stories because they feel like it’s a safe place and that’s what I was looking for and love the most.

The reason why I added the word queer to my username is because I wanted to make that statement publicly. We are often pushed into darkness and hiding and even when we are out there making content and even when we are essential to our communities, we are always pushed to stay hidden. I wanted to make that statement and say “I am not afraid”. The reality of it is that, of course, I am afraid, the laws are against me, we are oppressed and it’s dangerous but we exist. Queer people still exist, we’re here, fighting and I’m not ashmed of it. It was a big switch for me because I freed myself. Even after coming out as gay, I couldn’t free myself from the shame.

A lot of people ask me how I am able to be more or less out as the fact that I have Queer in my Instagram bio. I have Queer in my bio but not written in Arabic and that is privilege again.

Ever seen high school people that went to foreign school? They have seen [Queer] people and [those who] identify as Queer, so it existed in their environement in one way or another; I have not seen that. The first time that I heard someone saying “I’m Queer” is the time I realized I was Queer myself, that’s how awful it was.

All the Queer men that I met abroad from wealthier backgrounds, we never discussed our story. I will always feel like their stories were lighter. I was like 'WOW, why are you ok with yourself since you’re 16/18, how did you do that', I still have doubt to this day.

But the link with all of these people was that they were from wealthy families and went to private or foreign schools. Their environment was just safer".

Why are the upper classes not fighting?

It remains confusing how homosexuality is tolerated amongst the most affluent families, whose generations are moving towards modernity, yet this elite does not fight for the laws and all these injustices and inequalities to change. In upper class families, the parents have learnt tolerance or at least may be aware of how to be perceived as tolerant if social masking is the accepted way of moving forward. They have been exposed to other ways of life.

Although for Villaume, they have integrated other norms and values for the well-being of their children as a result, it is not enough for them to fight, it’s actually the opposite:

“Rich parents protect their children by keeping their mouths shut because the problem is that the elite want to keep their place. When you’re a part of the wealthy people in Morocco, there’s a lot of hypocrisy. Even if being gay is tolerated, they will not show it just to keep their privilege. They do not want the lower class to reach their privileges and for that they will not put themself in uncomfortable situations".

In stark contrast, the underprivileged will assume being gay and here’s the reason for it:

"The medina is extremely conservative. They have not traveled and haven't got access to good quality education. In this 'other' Morocco, far from the clubs of the modern city and the luxury cars, it’s like if the Sharia law (religious laws) are being applied."

"I would say that this is a fight led by the poor because their parents don't listen to them, their homosexuality is still considered as an illness, no one is actually listening to them, everything is against them. They have nothing to lose, they will lead the fight.” - Villaume

The call for revolution

After the wave of violence targeting members of the LGBTQ+ community during the lockdown of 2020, writers, artists and activists, both anonymous and public figures, have expressed their anger through articles, letters and manifestos in a book entitled "L"Amour Fait Loi" with means “Love makes laws''. The heartfelt cry of sexual minorities in Morocco includes activists like Abdellah Taia, Sofiane H and many more (see in the poster on this page for the full list of names).

I find this book to be devastating; You can hear while reading the pleas of this Moroccan LGBTQ+ community for the respect of their rights. Nevertheless, it is filled with hope, encapsulated by a pained call for revolution. Now this community has nothing to lose, they are not afraid. I questioned each person I interviewed on how they percieve an upcoming revolution so, let's start with the person at the heart of it all; Abdellah Taïa.

“When you meet a Moroccan in the street, he will give you the impression that he is conservative and that he respects the King and the religion. You have to look beyond that because if you stop at this impression, you get the impression that it's a hell. In reality, they are smarter and they manage within the political limits imposed on them. I think that we must always see in this art of sneaking, the possibility for a change; In another word, hope. Even the smallest movement is the one we need to see, look at, and raise.

The political world continues to deny the obvious but the obvious is here and things are moving little-by-little, whether the authorities want it or not. There are incredible people, people who have nothing and who, in spite of that, are ready to lose everything and put themselves in danger for their rights".

For Sofiane H, the fact that the rich don't want to revolt is not such a bad thing:

“There are a thousand and one ways to think about the next revolution. Personally, I see this revolution in the form of speaking out. That is to say, more and more people are speaking out and this is really qualitatively and quantitatively valid here. A few years ago, there were very few people like Abdellah Taia but today, we see individuals coming out [and] also groups and movements that are taking more and more space in the public debate which this is creating a real revolution. This revolution is taking place and what characterises it is, above all, the fact that we are no longer ashamed. Finally being queer, gay, lesbian etc. is no longer a problem. Of course, it is still a problem for the heteronormative system, i.e. legal, police or conservative people. It will change even if the system is against us for the moment".

"At present, we are really far from the French-speaking activist who has come to live abroad and who claims the rights of LGBTQ+ people in Morocco. We find trans people, poor people who did not go to university and therefore have no privileges at all, who speak out and talk about their situation, their experiences, their life as a queer person, and I think that the more we are in this model, the closer we are to liberation and emancipation".

"When revolutions are led by people who are concerned, who live it on a daily basis, when they walk in the street, when they go to the hospital or to school and who talk about their experience, and who militate and make a plea through what they live, I think it's a much stronger model. We are no longer in the model of a rich hetero, who will liberate the poor queer, but in a model that proves to us that the queer person is capable of fighting for his rights. no matter their social status”.

Last but not least, the next generation, the young activist said that, for him, the revolution is already here:

"The revolution is everywhere, it’s hidden as a lot of revolutions but just the fact that I exist, that queer people exist, that Abdellah Taia exists, is revolution in itself. I feel like a lot of the time we want that radical change but we’re not going to get that. We might not even see the end of it in our lifetime but little wins happen on a daily basis when we allow ourselves to exist in that system: When I kiss a partner, that’s a win; When I’m sharing my opinions, that’s a win; When I care for other queer people, that’s a win because those are the things that the system is failing to do. The system isn’t caring for queer people, it’s not listening to them or giving them a voice".

"The system will crack at some point. You feel the pressure and you feel that things cannot stay the same as they are now. Morocco is so eager to stay at the international track".

"We have a responsibility to keep the conversation alive, every single one of us, if we want change. I would be way more satisfied with my platform if I was writing in Arabic so that everybody could be included".

Cover of the book "L'amour fait loi" by Zaineb Fasiki

Cover of the book "L'amour fait loi" by Zaineb Fasiki

Mosaic of the authors of "Love Makes Laws"

Mosaic of the authors of "Love Makes Laws"

Fagouta "Stop queer hunting" (April,2020)

Fagouta "Stop queer hunting" (April,2020)

Ines Bouallou "Queer Revolution" (2020)

Ines Bouallou "Queer Revolution" (2020)

Zaineb Fasiki " L'Amour fait loi" (2020)

Zaineb Fasiki " L'Amour fait loi" (2020)

"Love is not a crime, it will win". -Unnamed Influencer